Ninth Circuit Determines That Persons Who Can’t Sit for More than Four Hours Can’t Perform Sedentary Work

In a previous post, we summarized the five exertion levels (sedentary work, light work, medium work, heavy work, and very heavy work), as defined by the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT), and discussed why they matter in the context of disability claims. Essentially, these exertion levels function as broad classifications that are used to categorize particular jobs and occupations. The physical requirements under each exertion level increase as you move up from level to level, with sedentary work requiring the least physical exertion and very heavy work requiring the most physical exertion.

If you have an “own occupation” policy, these exertion levels will likely not come into play, because the terms of your policy will require your insurer to consider the particular duties of your specific occupation, as opposed to the broader requirements of the various exertion levels. However, if you have an “any occupation” policy, which requires you to establish that your disability prevents you from working in any capacity, your insurer will likely seek to determine your restrictions and limitations at the outset of your claim, using claim forms or possibly a functional capacity evaluation (FCE). Once they have done so, they will then likely seek to fit you into one of the five exertion levels listed above and have their in-house vocational consultant provide them with a list of jobs that you can perform given your limitations.

Not surprisingly, your insurer will generally try to fit you into the highest category possible, and then argue that you can perform all of the jobs at that exertion level, and all jobs classified at a lower exertion level. Typically, someone suffering from a disabling condition can easily establish that they cannot perform medium, heavy, or very heavy work, so, in most cases, the insurer will be trying to establish that you can perform light work, or sedentary work, at the very least.

As you might expect, one of the key differences between sedentary and light work is that sedentary work mostly involves sitting, without much need for physical exertion, whereas light work involves a significant amount of walking and standing, in addition to other physical requirements, such as the ability to push or pull objects and the ability to operate controls. Given the low physical demands of sedentary work, it can often be difficult to establish that you cannot perform sedentary work. This can be problematic, because there are many jobs that qualify as sedentary work. However, if you have a disability that prevents you from sitting for extended periods of time, the very thing that makes sedentary work less physically demanding—i.e. the fact that you can sit during the job—actually ends up being the very reason why you cannot perform sedentary work.

While this is a common sense argument, many insurance companies refuse to accept it and nevertheless determine that claimants who cannot sit for extended periods of time can perform sedentary work. However, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals recently held in Armani v. Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company that insurers must consider how long a claimant can sit at a time when assessing whether they can perform sedentary work.

Avery Armani was a full-time controller for the Renaissance Insurance Agency who injured his back on the job in January 2011. He eventually stopped working as a result of the pain from a disc herniation, muscle spasms, and sciatica. Multiple doctors confirmed that Avery was unable to perform the duties of his job, which required him to sit for approximately seven hours per day. In July 2011, Northwestern Mutual classified Avery’s occupation as “sedentary” and approved his claim under the “own occupation” provision of his employer-sponsored plan.

Despite regular statements to Northwestern Mutual from his doctor that he could only sit between two and four hours a day and must alternate between standing and sitting every thirty minutes, Avery’s disability benefits were terminated in July 2013. Northwestern Mutual’s claims handler identified three similar positions in addition to Avery’s own position that he could perform at a “sedentary” level, and determined that his condition no longer qualified as a disability under his policy.

When his benefits were terminated, Avery sued Northwestern Mutual. After several years, his case ultimately reached the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. In resolving the case, the Ninth Circuit held that an individual who cannot sit more than four hours in an eight-hour workday cannot perform “sedentary” work that requires “sitting most of the time.” In reaching its conclusion, the Ninth Circuit cited seven other federal courts that follow similar rules, including the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, the District of Oregon, the Central District of California, the Northern District of New York, the Southern District of New York, and the District of Vermont.

While this case is not binding in every jurisdiction, it does serve to reinforce the common sense argument that a claimant who cannot sit for extended periods of time due to his or her disability cannot perform sedentary work. Additionally, though this rule was created in the context of a disability insurance policy governed by ERISA, the court did not qualify its definition or expressly limit its holding to cases involving employer-sponsored policies. Accordingly, in light of this recent ruling, it would be reasonable to argue that a court assessing an “own occupation” provision of an individual policy should similarly consider whether sitting for extended periods of time is a material and substantial duty of the insured’s occupation. If it is, and the insured has a condition that prevents him or her from sitting for more than four hours of a time—such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or chronic pain due to degenerative disc disease—then the insured arguably cannot perform his or her prior occupation and is entitled to disability benefits.

In short, the Armani case is noteworthy because its reasoning could potentially be applied to not only ERISA cases, but also disability cases involving individual policies and occupations—such as oral surgeon, endodontist, periodontist, attorney, accountant, etc.—that require the insured to sit for long periods of time in order to perform the occupation’s material duties. It will be interesting to see if, in the future, courts expand the Armani holding to cases involving individual policies outside of the ERISA context.

—————————

Source: Armani v. Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company, No. 14-56866, 2016 WL 6543523 (2016)

Can Your Disability Insurance Company Dictate The Medical Treatment You Must Receive To Collect Benefits? Part 4

Care Dictation Provisions

Throughout this series of posts we’ve addressed the increasingly restrictive medical care provisions in disability insurance policies. In Part 1, we discussed the evolution of the care standard and its effect on an insured’s ability to collect disability benefits and control their own medical treatment. In Part 2 we looked at the “regular care” standard, which places no obligation on the insured to undergo any unwanted medical treatment. In Part 3 we looked at the “appropriate care” and “most appropriate care” standards, which require much more vigilance on the part of policyholders, because they must be prepared at any time to establish that the treatment they are receiving is justified under the circumstances. In this final post, we are going to look at the most aggressive and intrusive language that has been adopted by disability insurance companies in an effort to dictate the care of their policyholders.

Here is an example of a very strict care provision, taken from a Great West disability insurance policy:

Regular Care of a Physician means personal care and treatment by a qualified Physician, which under prevailing medical standards is appropriate to the condition causing Total Disability or Residual Disability. This care and treatment must be at such intervals as will tend to lead to a cure, alleviation, or minimization of the condition(s) causing Total Disability or Residual Disability and which will lead to the Member’s return to the substantial and material duties of his own profession or occupation or maximum medical improvement with appropriate maintenance care.

Clearly, this provision was designed with one goal in mind: to give the insurer nearly unlimited power to scrutinize a policyholder’s course of treatment, including the ability to insist that any given procedure is necessary to cure or minimize the disability and maximize medical improvement. It is easy to see how a disability insurer might invoke this provision to assert its control over the medical decision making of their policyholder and use the leverage of disability benefit termination and claims denial to dictate their treatment.

Imagine that you are a surgeon with a herniated disc in your cervical spine, and that your policy contains the provision cited above. Your insurer insists that a fusion of the surrounding vertebra is the procedure most likely to alleviate your disability. Your doctor disagrees, recommending a more conservative course of treatment, such as physical therapy, modified activity and medication, such as muscle relaxants. Your doctor also warns you that if you have the surgery, you will experience reduced mobility and risk adjacent segment degeneration. However, your disability benefits are your only source of income. Fearing a claim denial, you agree to the procedure despite your doctor’s concerns. This results in a no-lose scenario for the disability insurer.

The best case scenario, from your insurer’s perspective, is that the surgery (for which you bore all the risk both physically and financially) is successful and you are no longer disabled. At worst, the procedure fails and the insurer merely has to pay the disability benefits it was obligated to pay to you in the first place. For you, however, an unsuccessful procedure can mean exacerbation of your condition, increased pain, and prolonged suffering. It is therefore vital that you understand your rights under your disability insurance policy.

Insurers are risk-averse by nature, and disability insurance is no different. Modern disability insurance policies, and particularly the medical care provisions, are designed to minimize the financial risk to the insurer. Disability insurers place an enormous burden on claimants to prove that their course of treatment meets the rigorous standards in their policy. Though stringent policy language can make it significantly more difficult to obtain the disability benefits you are entitled to, it does not strip you of your right to make your own medical decisions.

In order to preserve your medical autonomy in the disability claims process, you must become familiar with the details of your disability insurance policy before filing a disability claim. Understanding the terms of your disability insurance policy—including the care provision in your policy—is critical to successfully navigating a disability claim. You need to be familiar with your policy’s care requirements from the outset, so that you can communicate effectively with your physician to develop a plan of treatment that you are comfortable with and that comports with the terms of your disability insurance policy.

Even if you have a basic understanding of your rights under your disability insurance policy, it can be daunting to deal with an insurer that is aggressively seeking to dictate your medical care. In some cases, you may be forced to go to court to assert your right to make your own medical decisions—particularly if your policy contains one of the more recent, hyper-restrictive care provisions like the Great West provision above. Insurers know this, and they also know that most claimants are in no position to engage in a protracted court battle over whether they are receiving appropriate care. However, simply submitting to the medical mandates of your insurer to avoid the stresses and costs associated with litigation can have drastic consequences, depending on the nature of the medical care you are being asked to submit to. If you should find yourself in this difficult position, you should contact an experienced disability insurance attorney. He or she will be able to inform you of your rights under your disability policy and help you make an informed decision.

Can Your Disability Insurance Company Dictate The Medical Treatment You Must Receive To Collect Benefits? Part 3

“Appropriate Care” and “Most Appropriate Care”

In this series, we are looking at the different types of care provisions disability insurers insert into their policies so that they can later argue that they have a right to dictate the terms of your medical care. In Part 1, we discussed how many policyholders do not even realize that their disability insurance policy contains a care provision until the insurance company threatens to deny their claim for failure to obtain what the insurer perceives as sufficient medical care. We also discussed how care provisions have evolved over time to become more and more onerous to policyholders. In Part 2, we looked at one of the earliest and least stringent care provisions—the “regular care” provision—in detail.

In this post, we will be looking at a stricter care provision—the “appropriate care” provision. Here is an example of a typical “appropriate care” provision:

“Appropriate Care means you are receiving care by a Physician which is appropriate for the condition causing the disability.”

Disability insurance carriers implemented this policy language to allow their claims handlers and in-house doctors to weigh in on the type and quality of care their policyholders receive. As you’ll remember from Part 2 of this series, “regular care” provisions only required policyholders to be monitored regularly by a physician. Thus, under a “regular care” provision, as long as the policyholder was seeing a doctor, the insurer could not scrutinize or direct his or her treatment. Only by changing the policy language could they hope to have greater influence over the medical decisions of their policyholders.

This prompted disability insurers to add the additional requirement that the care must be “appropriate.” But what is “appropriate?” If you are suffering from cervical spinal stenosis, you likely have several reasonable treatment options available to you. For example, your physician might recommend physical therapy, but also indicate that you would be a candidate for more invasive treatment, such as steroid injections. If you have an “appropriate care” provision, does that mean that your disability insurer gets to decide which treatment you receive?

When presented with this question, most courts determined that “appropriate care” limits the insurer’s review of its policyholder’s care to whether it was necessary and causally related to the condition causing the disability.[1] Courts also held that “appropriate” care does not mean perfect care or the best possible care—it simply means care that is suitable under the circumstances.[2] Thus, if physical therapy, steroid injections, and surgery are all suitable treatments for cervical stenosis, most courts agree that your insurer cannot deny your disability claim or terminate your benefits based upon your decision to undergo a course of treatment they view as less effective than another.

In response to these cases, disability insurers again modified their policy language and created the “most appropriate” care provision. Here is an example of what a “most appropriate” care provision looks like:

“[You must receive] appropriate treatment and care, which conforms with generally accepted medical standards, by a doctor whose specialty or experience is the most appropriate for the disabling condition.”

This change places significant restrictions on a claimant’s autonomy not only because it limits the type of physician the claimant may choose, but because it restricts the claimant’s medical care to a singular “appropriate” course of treatment.

These types of provisions can make collecting disability benefits extremely difficult. For example, take the experience of Laura Neeb, a hospital administrator whose chemical sensitivity allergies became so severe that they rendered her totally disabled. After one of her doctors—Dr. Grodofsky—concluded that she had no identifiable allergies, Ms. Need sought another opinion from Dr. William Rea, founder of the Environmental Health Center in Dallas, Texas. Dr. Rea concluded that Ms. Neeb’s hypersensitivity to chemicals was so severe that she was “unable to engage in any type of work,” and required extensive treatment to manage the condition. Ms. Neeb’s insurer, Unum, nonetheless denied the disability claim. The court ultimately held that Ms. Neeb failed to obtain the “most appropriate care” by treating with Dr. Rea, agreeing with Unum that Dr. Grodofsky’s conclusions were correct.[3]

Ms. Neeb’s case illustrates just how restrictive the “most appropriate care” provision can be. It places the burden squarely on the policyholder to show that their chosen course of treatment and treatment provider are most appropriate for their condition. If your disability insurance policy contains a “most appropriate care” provision, it is essential that you find a qualified, supportive treatment provider who is willing to carefully document your treatment and the reasoning behind it. You do not want to place yourself in a position where you cannot justify the treatment you are receiving and must choose between an unwanted medical procedure and losing your benefits.

In the final post of this series, we will discuss the hyper-restrictive care provisions appearing in disability insurance policies being issued today and the serious threats they pose to patient autonomy.

[1] 617 N.W.2d 777 (Mich. Ct. App. 2000)

[2] Sebastian v. Provident Life and Accident Insurance Co., 73 F.Supp.2d 521 (D. Md. 1999)

[3] Neeb v. Unum Life Ins. Co. of America, 2005 WL 839666 (2005).

Can Your Disability Insurance Company Dictate The Medical Treatment You Must Receive To Collect Benefits? Part 2

“Regular Care”

If you are a doctor or dentist and you bought your individual disability insurance policy in the 1980s or 1990s, the medical care provision in your policy likely contains some variation of the following language:

“Physician’s Care means you are under the regular care and attendance of a physician.”

This type of care provision is probably the least stringent of all the care provisions. If your disability insurance policy contains a “regular care” provision, courts have determined that you are under no obligation to minimize or mitigate your disability by undergoing medical treatment.[1] In other words, you cannot be penalized for refusing to undergo surgery or other procedures—even if the procedure in question is minimally invasive and usually successful.[2]

Let’s look at an actual case involving a “regular care” provision. In Heller v. Equitable Life Assurance Society, Dr. Stanley Heller was an invasive cardiologist suffering from carpal tunnel syndrome who declined to undergo corrective surgery on his left hand. Equitable Life refused to pay his disability benefits, insisting that the surgery was routine, low risk, and required by the “regular care” provision of Dr. Heller’s policy. The U.S. Court of Appeals disagreed, and determined that the “regular care” provision did not grant Equitable Life the right to scrutinize or direct Dr. Heller’s treatment. To the contrary, the Court held that “regular care” simply meant that Dr. Heller’s health must be monitored by a treatment provider on a regular basis.[3]

Unfortunately, the Heller case didn’t stop insurance companies from looking for other ways to control policyholders’ care and threaten denial of benefits. For instance, some disability insurance providers argued that provisions requiring policyholders to “cooperate” with their insurer grants them the right to request that a policyholder undergo surgery. Remarkably, when insurers employ these tactics, they are interpreting the policy language in the broadest manner possible–even though they know that the laws in virtually every state require that insurance policies be construed narrowly against the insurer.

Why would insurance companies make these sorts of claims when it is likely that they would ultimately lose in court? Because insurance companies also know that even if their position is wrong, most insureds who are disabled and/or prohibited from working under their disability policy cannot handle the strain and burden of protracted litigation. They know that if they threaten to deny or terminate disability benefits, many insureds will seriously consider having surgery—if only to avoid the stress and expense of a lawsuit. Unfortunately, this can lead to insureds submitting to unwanted medical procedures, despite having no legal obligation to do so.

As time went on, and more and more courts began to hold that “regular care” simply meant that the insured must regularly visit his or her doctor, Unum, Great West, Guardian, and other insurers stopped issuing policies containing that language. Instead, disability insurers started to insert “appropriate care” standards into policies. In the next post, we will discuss this heightened standard and how disability insurers predictably used it as a vehicle to challenge the judgment of policyholders’ doctors, in a renewed effort to dictate their policyholders’ medical care.

[1] Casson v. Nationwide Ins. Co., 455 A.2d 361, 366-77 (Del. Super. 1982)

[2] North American Acc. Ins. Co. v. Henderson, 170 So. 528, 529-30 (Miss. 1937)

[3] Heller v. Equitable Life Assurance Society, 833 F.2d 1253 (7th Cir. 1987)

Can Your Disability Insurance Company Dictate The Medical Treatment You Must Receive To Collect Benefits? Part 1

Imagine that you are a dentist suffering from cervical degenerative disc disease. You can no longer perform clinical work without experiencing excruciating pain. You have been going to physical therapy and taking muscle relaxers prescribed by your primary care doctor, and you feel that these conservative treatments are helping. Like most dentists, you probably have an “own occupation” disability insurance policy. You are certain that if you file your disability claim, your insurer will approve your claim and pay you the disability benefits you need to replace your lost income and cover the costs of the medical treatment that has provided you with relief from your pain and improved your quality of life.

You file your disability claim, submit the forms and paperwork requested by the insurer, and wait for a response. To your dismay, your disability insurer informs you that its in-house physician has determined that the treatment prescribed by your doctor was inadequate. Your insurer then tells you that you should have been receiving steroid injections into your cervical spine, and tells you that if you do not submit to this unwanted, invasive medical procedure, your disability claim could be denied under the “medical care” provision in your policy.

You were not aware that such a provision existed, but, sure enough, when you review your policy more carefully, you realize that there is a provision requiring you to receive “appropriate medical care” in order to collect disability benefits. You think that your insurer is going too far by dictating what procedures you should or should not be receiving, but you are afraid that if you don’t comply with their demands, you will lose your disability benefits, which you desperately need.

This is precisely the sort of scenario presented to Richard Van Gemert, an oral surgeon who lost the vision in his left eye due to a cataract and chronic inflammation. Dr. Van Gemert’s disability insurance policies required that he receive care by a physician which is “appropriate for the condition causing the disability.” After years of resisting pressure from his insurers to undergo surgery, Dr. Van Gemert finally capitulated. Once Dr. Van Gemert received the surgery, you might expect that his insurer would pay his claim without further complaint. Instead, Dr. Van Gemert’s insurer promptly sued him to recover the years of disability benefits it had paid to him since it first asserted that he was required to undergo the surgery.[1]

Unfortunately, “appropriate care” provisions, like the provision in Dr. Van Gemert’s policy, are becoming more and more common. The language in such provisions has also evolved over time, and not for the better. In the 1980s and 1990s, the simple “regular care” standard was commonplace. In the late 1990s and into the 2000s, insurers began using the more restrictive “appropriate care” standard. And, if you were to purchase a policy today, you would find that many contain a very stringent “most appropriate care” standard.

These increasingly onerous standards have been carefully crafted to provide disability insurers with more leverage to dictate policyholders’ medical care. However, there are several reasons why your insurance company should not be the one making your medical decisions. To begin, if you undergo a surgical procedure, it is you—and not the insurance company—who is bearing both the physical risk and the financial cost of the procedure. Perhaps you have co-morbid conditions that would make an otherwise safe and routine surgical procedure extremely risky. Perhaps there are multiple treatment options that are reasonable under the circumstances. Perhaps you believe conservative treatment provides better relief for your condition than surgery would. These are decisions that you have a right to make about your own body, regardless of what your disability insurer may be telling you.

In the remaining posts in this series, we will be looking at the different types of care provisions in more detail, and how far insurance companies can go in dictating your care in exchange for the payment of your disability benefits. We will also provide you with useful information that you can use when choosing a disability insurance policy or reviewing the policy you have in place. In the next post we will be discussing the “regular care” standard found in most policies issued in the 1980s and early 1990s.

[1] See Provident Life and Accident Insurance Co. v. Van Gemert, 262 F.Supp.2d 1047 (2003).

The Devil Is In the Details: Long Term Disability Policies and Benefit Offsets

In a previous post, we discussed a feature of long-term disability insurance policies that is easily overlooked and frequently leaves policyholders feeling cheated and deceived by their insurer: the benefit offset provision. When a person signs up for a disability insurance policy, he or she expects to pay a certain premium in exchange for the assurance that the insurance company will provide the agreed-upon monthly benefit listed in the policy, should they ever become disabled. What many people do not realize is that some disability insurance policies contain language that permits the insurer to reduce the amount of monthly disability benefits it is required to pay if the policyholder receives other benefits from another source.

Worker’s compensation, supplementary disability insurance policies, state disability benefits, and social security are some of the most common “other sources” from which policyholders may unexpectedly find their disability insurance benefits subject to an offset. The frequency of offset provisions varies by policy type. They are more likely to appear in group policies and employer-sponsored ERISA policies, and are rarely found in individual disability insurance policies.

Benefit offset provisions can have significant and often unforeseen financial repercussions, as illustrated by the recent account of a couple from Fremont, Nebraska. As reported by WOWT Channel 6 News, Mike Rydel and his wife Carla were receiving monthly benefits under Mr. Rydel’s disability insurance policy with Cigna. Mr. Rydel had suffered a stroke in the fall of 2015 that had left him incapacitated and unable to work. The Rydels’ financial situation was made even more dire by Mr. Rydel’s need for 24-hour care, which prevented Mrs. Rydel from working as well.

In an effort to supplement his family’s income, Mr. Rydel applied for Social Security disability benefits. When his claim was approved, the Rydels expected a much needed boost to their monthly income. Unfortunately, due to an offset provision in Mr. Rydel’s policy, his monthly disability benefits under the Cigna policy were reduced as a result of the approved Social Security claim, and his family did not realize any increase in income.

The Rydels were understandably shocked when they were informed by Cigna that Mr. Rydel’s monthly disability insurance benefits would be reduced by the amount he was now receiving from Social Security, and that Cigna would be pocketing the difference. Perversely, the only party that benefited from Mr. Rydel’s SSDI benefits was Cigna, which was off the hook for a portion of Mr. Rydel’s monthly benefits. In response to an inquiry from WOWT, Cigna simply asserted that “coordination” of private insurance benefits and government benefits was a long-standing practice – an assurance that likely provided no solace to the Rydels.

The Rydels’ story highlights the importance of carefully reviewing every aspect of your disability insurance policy before signing. Benefit offsets, policy riders, occupational definitions, and appropriate care standards in your policy can significantly impact your ability to collect full benefits if you become disabled. You should review your disability insurance policy carefully to determine if it contains any offset provisions that may affect your benefits. If it does, you will need to take them into account when estimating your monthly benefits.

References:

http://www.wowt.com/content/news/Stroke-Victim-Suffers-Disability-Insurance-Set-Back-385758411.html

Unum Study Shows an Increase in Musculoskeletal Disability Claims Over the Past Decade

As we have discussed in previous posts, musculoskeletal disorders are very common among dentists due to the repetitive movements and awkward static positions required to perform dental procedures. Unum, one of the largest private disability insurers in the United States, recently released statistics showing an increase in the filing of musculoskeletal disability claims over the past 10 years.

According to Unum’s internal statistics, long term disability claims related to musculoskeletal issues have risen approximately 33% over the past ten years, and long term disability claims related to joint disorders have risen approximately 22%. In that same period of time, short term disability claims for musculoskeletal issues have increased by 14%, and short term disability claims for joint disorders have risen 26%.

This trend may lead to Unum directing a greater degree of attention towards musculoskeletal claims as the volume of these claims continues to increase. Musculoskeletal claims are often targeted by insurance companies for denial or termination because they are easy to undercut—primarily due to the limitations of medical testing in this area. For instance, it can be difficult to definitively link a patient’s particular subjective symptoms to specific results on an MRI, and other tests, such as EMGs, are not always reliable indicators of the symptoms that a patient is actually experiencing. Insurers also typically conduct surveillance on individuals with neck and back problems in an effort to collect footage they can use to deny or terminate the claim. While such footage is usually taken out of context, it can be very difficult to convince the insurance company (or a jury) to reverse a claim denial once the insurer has obtained photos or videos of activities that appear inconsistent with the insured’s disability.

As we have noted in a previous post, Unum no longer sells individual disability insurance policies, so its disability insurance related income is now limited to the premiums being collected on existing policies. Because benefit denials and termination are the primary ways insurers like Unum can continue to profit from a closed block of business, and musculoskeletal claims are on the rise, Unum may begin subjecting this type of claim to even higher scrutiny.

References:

http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160505006009/en/Aging-obesity-tip-scales-10-year-review-Unum

Dealing with the Demands of Dentistry: It’s Ok to Ask for Help

Dentistry is not an easy profession. The clinical aspects of dentistry are physically and emotionally demanding. Performing repetitive procedures and holding static postures for prolonged periods of time can leave dentists feeling mentally drained, sore and fatigued. And given the frequent exposure to patient anxiety and the need for precision when performing dental procedures, it is not uncommon for dentists themselves to develop anxiety about causing pain to patients or making a mistake when performing a procedure.

The other aspects of dentistry are no less challenging. Many dentists work long hours, which makes balancing work, family, and other responsibilities difficult. Other stressors include difficult and uncooperative patients, dissatisfied patients, finances, business problems, collecting payments, paperwork/bureaucracy, time pressure, cancellations, no-shows—the list goes on and on. And that is not even taking into consideration major stressors, such as staff issues, board complaints, audits, and malpractice lawsuits.

When presented with these difficulties, dentists can become anxious and depressed. Some even seek out mood altering drugs and/or begin to abuse alcohol, in an effort to alleviate the stress.

Thankfully, there are resources available where dentists can turn to for help. Most dental associations have a subcommittee or group designed to provide confidential help to dentists struggling with emotional, mental and/or substance abuse issues.

For example, the Arizona Dental Association (AzDA) has a group called the Dentists Concerned for Dentist Committee (DCD). The DCD is a group of fellow dentists who work with other dentists to help them with substance abuse problems, with an emphasis on “cure and return to practice.” When the DCD is contacted, everything remains strictly confidential, and the State Board is not notified. As explained by the DCD, “[t]here should be no grief or shame in seeking help.” Accordingly, DCD records are “sealed and cannot be accessed by anyone.”

If you are a dentist in Arizona struggling with substance abuse, or you know a dentist who is, consider contacting the AzDA so that a referral can be made to the DCD. You can find the contact information for the AzDA here.

If you live outside Arizona, consider contacting your local dental association to see if it has a similar program.

Remember, it’s ok to ask for help.

References:

“When Life Feels Just Too Hard,” INSCRIPTIONS, Vol. 30, No. 8 (August 2016) at p. 24.

Thinking About a Policy Buyout?

How Lump Sum Settlements Work: Part 2

In this two-part series we are addressing the two most common scenarios in which insurance companies pursue lump sum buyouts. In Part 1, we talked about buyouts for individuals who are totally and permanently disabled and have been on claim for several years. In Part 2, we will address the other scenario in which buyouts occur: after a lawsuit has been filed.

In the context of an individual disability insurance policy, a lawsuit is generally filed in one of two common scenarios: (1) a person on claim with a legitimate disability has their benefits terminated; or, (2) a person with a legitimate disability has their claim denied. A lawsuit is typically considered to be the last line of defense in the disability claims process. By the time a lawsuit has been filed, the claimant’s attorney has likely exhausted every available means to resolve the claim without legal action. Litigation is costly, time-consuming, and can drag on for years.

If an insurance company offers a lump sum buyout during litigation, it will typically be at one of three stages in the case: (1) after the Complaint and Answer are filed; (2) after all stages of pretrial litigation and discovery are complete; or (3) after the claimant/plaintiff wins at trial.

The first stage of any lawsuit is the filing of the Complaint. This is a document the plaintiff files with the court outlining all of the claims and allegations against the defendant. After receiving a copy of the Complaint, the defendant then has a specified period of time in which to file an Answer responding to the plaintiff’s allegations.

Prior to the filing of a lawsuit, a contested claim has likely been reviewed only by the insurance company’s in-house attorneys. However, once litigation begins, the insurance company will retain a law firm experienced in insurance litigation to handle the case. After the filing of the Complaint, the insurance company’s outside counsel will have the opportunity to evaluate the strength of the case and the claim. Viewing the case through the prism of their experience, the insurer’s litigation team may recommend offering a buyout to avoid the risk, costs, and time associated with the lawsuit.

The second point of a lawsuit at which a buyout may occur is after all stages of pretrial litigation are complete. Once the parties have had the opportunity to conduct discovery and litigate any pretrial motions, they will have a full picture of the case and their prospects at trial. Through discovery both sides will be able to obtain all documents and interview all witnesses the other side intends to use at trial. Through the filing of pretrial motions the parties can attempt to prevent or limit the use of certain evidence or witnesses at trial.

At this juncture, the insurance company may seek to avoid the risks of trial and settle the claim before the first juror is ever impaneled. The disability insurance company’s incentive to resolve the case at this point – even after both sides have invested substantial resources in the litigation – is the financial exposure and bad publicity it faces with a loss at trial. Additionally, a bad result at trial for the insurance company could create undesirable legal precedent for future cases.

If a jury (or a judge, depending on the case) determines that the insurance company has unlawfully denied or terminated a legitimate disability claim, the insurer will not only be required to pay the disability benefits the claimant/plaintiff is entitled to, but may also be liable for damages and other costs. The disability insurer may be required to pay back benefits, plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees and costs, consequential damages, and punitive damages.

In the context of a disability insurance lawsuit, consequential damages come in the form of any financial harm to the claimant/plaintiff resulting from the insurer’s denial or termination of benefits. For example, if the insurer’s termination of benefits led to the claimant/plaintiff losing their house in foreclosure, the insurer could be liable for consequential damages. Punitive damages are designed to deter the insurer from denying legitimate disability claims in the future, and can be multiplied several times over if the insurer is found to have acted in bad faith. Additionally, some states allow acceleration of benefits – in which the courts can order the insurer to immediately pay future benefits that would owed to the claimant/plaintiff over the full life of the policy.

The final stage at which a lump sum buyout may be offered is after a victory at trial by the claimant/plaintiff. You may be wondering why anybody would entertain a settlement offer right after a being awarded back benefits, damages, and costs at trial – why accept anything less? The answer is simple: appeals. The insurance company can tie up a trial court victory in the court of appeals for years, which they can use as leverage to offer a settlement smaller than the trial award.

Though these three stages of litigation are the most common points at which a buyout may occur, buyouts themselves are uncommon during litigation. Depending on the situation, the specter of a long, drawn out legal battle can either provide the insurance company with the incentive to settle the lawsuit early with a buyout or harden its resolve to fight the claim to the bitter end. You cannot count on simply filing a lawsuit and expecting the insurance company to be eager to settle. Some insurance companies want to settle early and avoid the financial risks and bad publicity of a defeat at trial, while others take a hard line and use their nearly limitless resources to fight a war of attrition. Ultimately, whether or not a disability insurer offers a lump sum buyout in the midst of litigation depends largely on the individual facts of the case, the risks at trial, and the parties and attorneys involved.

Thinking About A Policy Buyout?

How Lump Sum Settlements Work: Part 1

Lump sum buyouts are a frequent source of questions from our clients and potential clients. With that in mind, the next few posts will address different aspects of the buyout process.

Buyouts typically occur in one of two situations: 1) after you’ve been on claim for several years, or 2) after a lawsuit has been filed. This blog post will focus on the first scenario.

Lump sum buyouts that occur outside of litigation normally won’t occur unless and until the insurance company decides that you are totally and permanently disabled under the policy definition. Typically, the disability insurer won’t consider whether this is the case until you’ve been on claim for at least two years. If the insurer determines that you’re totally and permanently disabled, it will then determine whether it makes sense financially for the company to offer you a percentage of your total future benefits rather than keep paying your monthly benefits for the entire duration of your claim.

To understand how the insurance company calculates whether a buyout is in its financial interest, you should understand how insurance company reserves work. The purpose of reserves is to ensure that the insurance company has the resources to fulfill its obligations to policyholders even if the company has financial difficulties. Thus, disability insurers are required by state regulators to keep a certain amount of money set aside, or “reserved,” to pay future claims. Any money required to be kept in a reserve is money that the insurer can’t spend on other things or pay out in dividends. The amounts required to be kept in the reserve are determined by the state, depending on factors like how much the monthly benefit is and how long the claim is expected to last.

For a disability insurance claim, a graph of the required reserve amount over time looks like a Bell curve: low at the beginning, highest in the middle, and low again towards the end of the benefit period. The ideal time for a settlement, from an insurance company’s perspective, is at or just before the high middle point–typically about five to seven years into the claim, depending on the claimant’s age and the duration of the benefit period. At this point, the company is having to set aside the highest amount of money in the reserve.

If the insurance company can pay you a percentage of your total future benefits, it can not only save money in the long run, but it can release the money in the reserve. The disability insurer can then use those funds for other purposes, including providing dividends for its investors. In addition, the insurance company will save all of the administrative expenses it was putting towards monitoring your disability claim.

In the next post, we’ll address how and why buyouts occur after a lawsuit has been filed.

Should Women Pay More for Disability Insurance? Part 2

In a previous post, we discussed how a woman with the same age, job and health history as a man can end up paying an average of 25% (and in some cases, 60%) more for the same level of disability insurance protection. We also discussed how some insurance companies raise premiums based on conditions unique to one’s sex, such as pregnancy.

When we first addressed this issue, the Massachusetts legislature was considering a bill that prohibited insurers from charging higher rates to women than to men. At the time, Massachusetts law prohibited insurance companies from using race and religion as rating factors when determining the cost of insurance, but there was no law against using gender as a rating factor.

Recently, the Massachusetts Senate voted to approve a budget amendment adding gender to other rating factors that insurance companies are not allowed to consider when determining the cost of premiums. The bill passed by a wide margin: 32 senators in favor of the amendment, and only 6 senators voting against the amendment.

It will be interesting to see if, in the future, other states follow suit and start to pass laws requiring insurance companies to give men and women the same premium rates for the same level of disability coverage.

References:

http://www.masslive.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/05/senate_votes_to_exclude_gender.html

Long Term Disability by Diagnosis

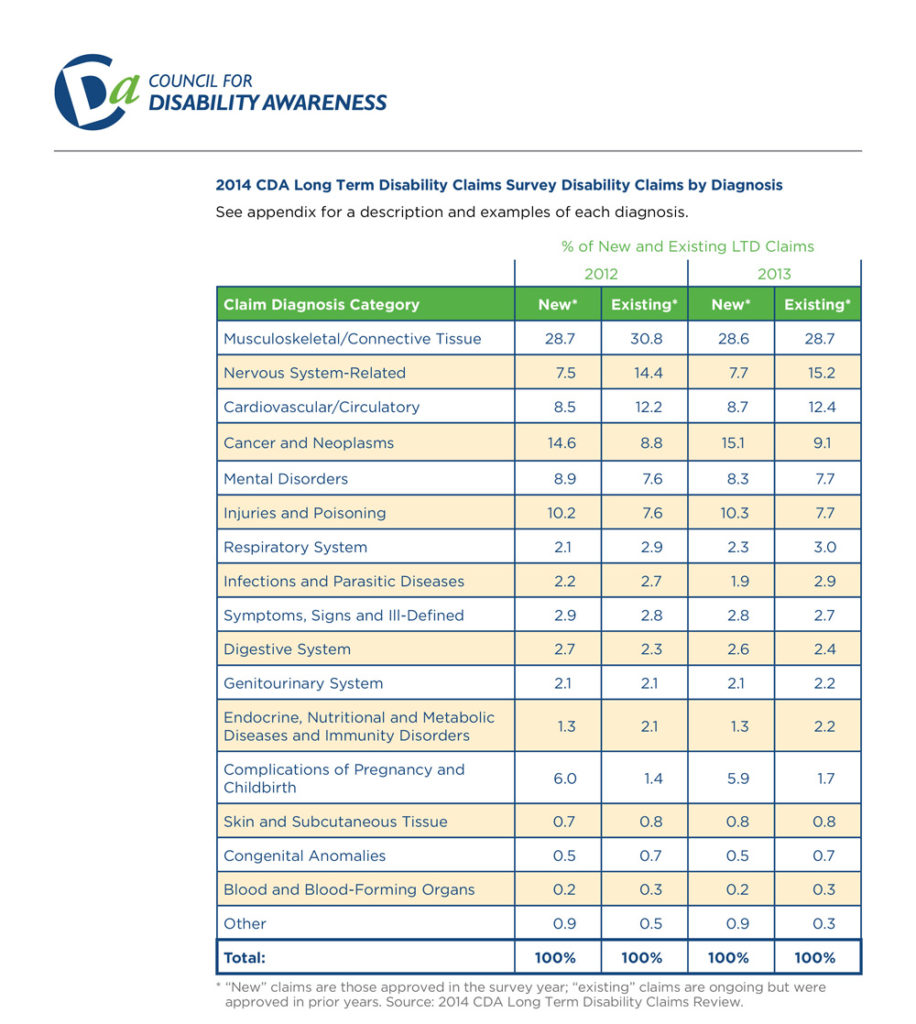

In previous posts, we have been looking at the findings from the most recent study on long term disability claims conducted by the Council for Disability Awareness. In this post we will be looking at the types of diagnoses associated with long term disability claims, and which types of claims are most common.

As you can see from the chart above, the most common type of both new and existing long term disability is musculoskeletal disorders—a category which includes neck and back pain caused by degenerative disc disease and similar spine and joint disorders.

This is particularly noteworthy because physicians and dentists, who often have to maintain uncomfortable static postures for several hours each day, are very susceptible to musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, claims involving musculoskeletal disorders can be challenging, because oftentimes there is little objective evidence to verify the pain. If you suffer from degenerative disc disease or a similar disorder, an experienced disability insurance attorney can explain how to properly document your disability claim to the insurance company.

References:

http://www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2014.asp

Case Study: Factual Disability v. Legal Disability – Part 3

In the last post, we discussed the facts of the court case Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company v. Jefferson[1]. In that case, the court was asked to determine whether a clinical psychologist whose license had been suspended was entitled to disability benefits. In this post, we will discuss how the court ultimately ruled, and go over some takeaways from this case.

The Court’s Ruling

As explained in the last post, the key question was whether Dr. Jefferson’s legal disability (i.e. the suspension of his license to practice psychology) happened before the onset of Dr. Jefferson’s factual disability (i.e. his depression). In the end, the court determined that Dr. Jefferson was not entitled to disability benefits for the following reasons:

- Dr. Jefferson’s claim form stated that he was not disabled until April 29, 1990, which was two days after the licensing board revoked his license.

- Although Dr. Jefferson later claimed that his depression went as far back as May 1989, the court determined that such claims were inconsistent with:

-

- Jefferson’s representations to the licensing board that he was a “highly qualified and competent psychologist”;

-

- The fact that Dr. Jefferson had been consistently seeing patients up until the day his license was revoked; and

-

- The fact that Dr. Jefferson had scheduled patients during the month following the licensing board’s hearing.

Thus, under the circumstances, the evidence showed that Dr. Jefferson’s was not entitled to benefits because his legal disability preceded his factual disability.

Takeaways

Dr. Jefferson’s case provides a good example of the challenges that can arise in a disability claim if the claimant has lost his or her license. Here are some of the major takeaways from this case:

Be Precise When Filling Out Claim Forms. The date you list as the starting date of your disability can be very significant. Take your time when filling out claim forms, and make sure that the date you provide is accurate and consistent with the other information you are submitting with your claim forms. It is always a good idea to double check everything on the form at least once after you have completed it, to make sure that you did not make a mistake.

Recognize that Your Claim Will Not Be Evaluated in a Vacuum. Other proceedings—such as board hearings—can directly impact your disability claim. You should always assume that anything you say in such a proceeding will at some point end up in front of the insurance company. This is particularly problematic when, as in Dr. Jefferson’s case, the goals of the other proceeding are inconstant with the goals of the disability claim. In such a situation, you may have to decide which goal is more important to you. An experienced disability insurance attorney can help you assess the strengths and weaknesses of each available option so that you can make an informed decision.

Do NOT Engage in Activities that Place Your License in Jeopardy. Losing a license that you worked hard for several years to obtain is not only emotionally devastating, it can severely limit your options going forward. Even if you have a disability policy, it is very difficult to successfully collect on a disability claim if your license has been revoked or suspended. Once again, if you find yourself in Dr. Jefferson’s position, you should talk with an experienced attorney who can help you determine what your available options are, if any.

[1] 104 S.W.3d 13, 18 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2002).

Case Study: Factual Disability v. Legal Disability – Part 2

In the last post, we discussed the distinction between “factual” and “legal” disability and why that distinction matters. In this post, we will begin looking at a court case involving “factual” and “legal” disability. Specifically, in this post we will begin looking at the facts of the case and the test that the court applied. In Part 3, we will see how the court ultimately ruled.

The Facts

In the case of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company v. Jefferson[1], the court assessed whether Dr. Jefferson—a clinical psychologist—was entitled to disability benefits. Here are the key facts of the case:

- From October 1987 to February 1989, Dr. Jefferson had an affair with a former patient.

- When Dr. Jefferson’s wife found out about the affair, she filed a complaint with Dr. Jefferson’s licensing board.

- During the hearings in front of the licensing board, Dr. Jefferson argued that he was a competent psychologist, and that he should be permitted to continue to see patients.

- On April 27, 1990, the licensing board permanently revoked Dr. Jefferson’s license to practice psychology, effective as of May 15, 1990. On appeal, a chancery court reduced the permanent revocation to an eight year suspension ending on May 15, 1998.

- Up until the day his license was revoked, Dr. Jefferson continued to see patients and schedule future patients.

- On October 1, 1990, Dr. Jefferson filed a claim under his disability policy, claiming that he was disabled due to “major depression.”

- On his claim form, Dr. Jefferson listed the beginning date of his disability as April 29, 1990. Later on, Dr. Jefferson attempted to submit evidence that he had been depressed as early as May 1989.

The Court’s Test

As a threshold matter, the Court determined that the suspension of Dr. Jefferson’s license was a “legal disability” and assumed for the sake of argument that Dr. Jefferson’s “major depression” was a “factual disability.” As explained in Part 1 of this post, courts generally hold that disability policies only cover factual disabilities, not legal disabilities. However, the court’s decision becomes more difficult when a claimant like Dr. Jefferson has both a legal disability and a factual disability.

Although different courts approach this situation in different ways, here is the test that the court came up with in Dr. Jefferson’s case:

- Step 1: Determine which disability occurred first.

- Step 2: Apply the following rules:

-

- Rule # 1: If the legal disability occurred first, the claimant is not entitled to benefits.

-

- Rule # 2: If the factual disability occurred first, the claimant is entitled to benefits, if the claimant can prove the following three things:

-

-

- The factual disability has medical support.

- The onset of the factual disability occurred before the legal disability.

- The factual disability actually prevented or hindered the claimant from engaging in his or her profession or occupation.

-

In the next post, we will discuss how the court decided this case. In the meantime, now that you have the key facts and the court’s test, see if you can guess how the court ultimately ruled.

[1] 104 S.W.3d 13, 18 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2002).

Case Study: Factual Disability v. Legal Disability – Part 1

In the next few posts we will be looking at the distinction between “factual” and “legal” disability. In Part 1, we will discuss the difference between a factual and a legal disability, and why that distinction matters. In Parts 2 and 3, we will look at an actual court case involving “factual” and “legal” disability.

What is “Factual Disability”?

Factual disability refers to incapacity caused by illness or injury that prevents a person from being physically or mentally able to engage in his or her occupation. This is the type of disability that most people think of in connection with a disability claim.

What is “Legal Disability”?

Legal disability is a broad term used to encompass all circumstances in which the law does not permit a person to engage in his or her profession, even though he or she may be physically and mentally able to do so. Here are some examples:

- Incarceration;

- Revocation or suspension of a professional license;

- Surrendering a professional license as part of a plea agreement or to avoid disciplinary action; and

- Practice restrictions imposed by a licensing board.

Why the Distinction Matters

In sum, someone with a “factual disability” is mentally or physically unable to engage in their profession. In contrast, someone with a “legal disability” is not allowed to engage in their profession. Courts have repeatedly held that disability insurance policies provide coverage for factual disabilities, but not for legal disabilities.

If a claimant has both a factual and legal disability, things become more complicated. In the next few posts, we will look at an example of how one court determined whether someone with both a factual and legal disability was entitled to benefits.

Online Underwriting – Tips to Avoid Potential Pitfalls

Recently, several disability insurers have started to introduce new online applications in an effort to make purchasing disability insurance more convenient. Some of them even offer automated underwriting and instant approval of your application. In connection with the online applications, insurers are also providing more flexible options regarding benefit amounts and benefit periods.

While online applications will likely make purchasing disability insurance more convenient, here are some tips to keep in mind and some pitfalls to avoid.

- Don’t neglect to shop around. While it will certainly take less time to just apply to the first website you come across, you should always look at what multiple companies are offering before you apply for disability benefits. While it may not seem like it at the time, the decision to purchase disability insurance may be one of the most important decisions in your life if you end up becoming disabled. So make sure to take the time to research what your options are, so that you can be sure to get the best disability insurance policy you are able to.

- Do the research. If you are merely interacting with a computer screen, you will not be able to ask questions about particular policy provisions. Consequently, you should take the time to do outside research so that you know exactly what to look for and what to avoid in a disability insurance policy.

- Don’t sacrifice important provisions for convenience or affordability. There are certain provisions that every doctor and dentist should have in their policy, such as an own occupation provision. If the online policy does not offer the provisions you need, don’t settle for the sake of convenience or affordability. Remember, if you end up becoming disabled, you will not just want any disability policy—you will want the best disability policy.

- Take your time when you are filling out your application. Most disability insurance policies contain language that allows the insurer to void the policy if you make material misstatements in your application. Many people tend to rush through online applications, particularly if their priority is convenience. Make sure that you double check your answers before you submit the application, to ensure that everything you are submitting is accurate.

- Periodically reevaluate your coverage. If your initial goal is affordability, make sure that you periodically reevaluate your coverage to ensure that it is still sufficient for your needs. Many people initially apply for low benefit policies and neglect to increase their benefits amounts later on when they can afford to pay higher premiums. Consequently, if they become disabled, their benefit amount ends up covering only a small fraction of their prior income.

These tips are particularly important for physicians and dentists to remember when applying for disability insurance, because insurance companies are particularly aggressive towards disability claims filed by doctors and dentists. Additionally, many doctors and dentists are accustomed to a high level of income. Physicians and dentists who do not purchase enough disability coverage and later become disabled can find themselves unable to meet their obligations and care for their family, even if their disability claim is approved. Additionally, as we have discussed in previous posts, in some cases, a single word in a disability insurance policy can determine whether you receive benefits.

So remember, purchasing disability insurance is not something that should be taken lightly. Take your time, and get the best policy you can.

What is a Pain Journal and Why Are They Important?

In previous posts, we have discussed the importance of properly documenting your disability. In this post we are going to discuss one way you can document your disability—pain journals.

A pain journal is exactly what is sounds like—a journal in which you document your pain levels and symptoms each day. Creating this sort of record will not only provide you with documentation when filing your disability claim, but will also allow you to effectively communicate with your treatment providers regarding your symptoms, so that they can provide you with appropriate care. Oftentimes, depending on your disability, you will go several days or weeks without speaking to your treatment providers. A pain journal can help you easily recall and communicate to your treatment provider everything that has happened since you last met with them.

Tips for Creating a Pain Journal

When creating a pain journal, you want to be as specific as possible so that your record is complete. You also want to make sure that you describe your plain clearly, so that you will be able to understand what you meant when you refer back to your journal.

Here are a few things you might consider documenting in your journal:

- The location of the pain.

- The level of the pain (if you use a numeric scale, be sure to also describe the scale).

- The duration of the pain.

- Any triggers to the pain.

- Any medications you are taking.

- Whether the medications you are taking are effective or have any adverse side effects.

- Any other symptoms in addition to the pain.

When filling out your pain journal, you may have a hard time coming up with a description that fits the type of pain you are experiencing, since all pain is not the same. However, you should avoid the temptation to document your pain in a generic way. The type of pain you are experiencing is just as important as your pain levels, and it is something that your disability insurer will likely ask you to describe.

To that end, here is a list of adjectives that are commonly used to describe pain:

Cutting; Burning; Cramps; Knots; Deep; Pulsing; Sharp; Shooting; Tender; Tight; Surface; Throbbing; Acute; Agonizing; Chronic; Dull; Gnawing; Inflamed; Raw; Severe; Stabbing; Stiff; Stinging

Sample Pain Journals:

American Pain Foundation Form:

American Cancer Society Form:

Peace Health Medical Group Form:

The Four Functions of Insurance

In this post, we are going to discuss the four functions of an insurance company.

Introduction – The Promise

Insurance is not like any other business. Rather than selling a tangible product that you receive immediately upon paying for it, insurance companies are selling an important promise—a promise of protection, security and peace of mind if something goes wrong.

When you buy a car, you give someone money and you take a car home. When you buy groceries, you pay money and get your groceries. Insurance is different. With insurance, you give them money and trust, and hope and pray that you never have to collect.

The Four Functions of Insurance

The activities of an insurance company can be divided into four major functions:

1. Actuarial

The actuarial department is concerned with what kind of promise the company is going to sell and how much the promise should cost. Essentially, the actuaries’ role is to analyze the financial consequences of risk and price the company’s product in a way that will allow the company to make a profit. For example, an actuary working for a car insurance company might calculate the risk that potential customers will be in a car accident, and then adjust premium amounts to account for that risk so that the insurer can pay accident claims and still make money.

2. Marketing

The marketing department is concerned with how to get people to buy the promise being sold. They design ads and employ sales people. Basically, this department’s goal is to get people interested in buying the promise.

3. Underwriting

The underwriting department determines who the company should sell the promise to. Underwriters review applications and assess whether the company should allow applicants to purchase the promise. For example, the underwriting department of a life insurance company might review health questionnaires submitted by applicants to assess whether the level of risk is low enough to provide life insurance to the applicant.

4. Claims

The claims department’s role is to process and pay legitimate claims. While the first three departments are very much concerned about profitability, the claims department is not supposed to consider company profitability when adjusting a claim. If the actuaries made a mistake and sold a product that is costing the company too much money, the product was not marketed correctly, or if underwriting was too lax, the company is supposed to pay legitimate claims and bear the loss.

Conclusion

As we have discussed in previous posts, an insurance company has a legal obligation to treat its customers fairly and deal with its customers in good faith. Ideally, the disability insurance claim process should be simple. You should inform the company that you meet the standards of the contract, provide certification from a doctor of that fact, and collect your disability benefits. It is not supposed to be an adversarial process.

Unfortunately, in instances where one or all of the first three departments mess up, some insurance companies improperly shift the burden of making a profit onto the claims department. This, in turn, transforms the claims process into an adversarial process.

If you have an experienced disability attorney involved from the outset of your disability claim, your attorney can monitor the insurance company to make sure that they are complying with their legal obligations. If you have already filed a disability claim, but believe that your insurer is not properly processing your claim, an experienced attorney can review the insurer’s conduct and determine whether the disability insurer is acting in bad faith.