Deciphering Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Policy Exclusions – Part 2

In Part 1, we looked at how disability insurance companies broadly define mental disorders and substance abuse. In this post, we will be looking at a sample mental disorder and substance abuse limitation provision.

What Does a Mental Disorder and Substance Abuse Limitation Look Like?

Here is a sample limitation provision from an actual disability policy (this provision is taken from the same policy containing the definition of “mental disorders and/or substance abuse disorders” discussed in Part 1):

maximum indemnity period means the maximum length of time for which benefits are to be paid during any period of total disability (see the Policy Schedule on Page 1). Benefits will not be paid beyond the policy anniversary that falls on or most nearly after your sixty-seventh birthday, or for 24 months, if longer, except as provided by this policy. In addition to any limitations described above, the maximum indemnity period for a disability due to a mental disorder and/or substance abuse disorder is also subject to the following limitations: (a) The lifetime maximum indemnity period is 24 months; (b) the 24-month limitation also applies to all supplementary benefits payable by virtue of your disability due to a mental disorder and/or substance abuse disorder; (c) any month in which benefits are paid for a mental disorder and/or substance abuse disorder (regardless of whether paid under the base policy any supplementary benefits or both) shall count toward the 24-month limitation; (d) this limitation applies to this policy and all supplementary benefits under this policy.

Note that this provision is not entitled “mental disorder limitation” or “substance abuse limitation.” Instead, it is entitled “maximum indemnity period.” In fact, this provision is actually part of the policy’s definition section, and not the main part of the policy—highlighting the importance of carefully reviewing the definitions in your disability insurance policy.

Note also that this particular provision provides that any month in which disability benefits are paid counts against the 24 month limit. So, for example, if you received disability benefits for a period of 12 months in connection with a substance abuse related disability, and subsequently returned to work, the next time you needed to file a claim related to a mental disorder or substance abuse, you could only receive a maximum of 12 months of disability benefits.

Conclusion

When purchasing a disability policy, watch out for mental disorder and substance abuse exclusions and limitations. Always be sure to ready your policy carefully so that you understand the scope of the protection you are purchasing. If you already have a disability policy, an experienced disability insurance attorney can review your policy and determine whether it contains any mental disorder or substance abuse limitations that might limit your ability to collect disability benefits under your policy.

Deciphering Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Exclusions – Part 1

In previous posts, we have discussed how many disability policies contain mental disorder and/or substance abuse exclusions that either prevent claimants from collecting disability benefits under their policies, or severely limit claimants’ right to collect—usually to 24 months or less.

Sometimes, it can be hard to tell if your disability insurance policy contains such an exclusion. Policy language can be difficult to decipher, and it becomes even more difficult in cases where the terms of the exclusion are contained within multiple provisions of the disability policy.

In the next few posts, we are going to discuss mental disorder and substance abuse exclusions. In Part 1, we will look at an example of how insurance companies define mental disorders and substance abuse. In Part 2, we will look at an example of a mental disorder and substance abuse limitation provision.

How Do Insurance Company’s Define Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse?

Each policy’s definition varies, depending on the insurance company. Here is a sample definition taken from an actual insurance policy:

mental disorders and/or substance abuse disorders mean any of the disorders classified in the most current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Such disorders include, but are not limited to, psychotic, emotional, or behavioral disorders, or disorders relatable to stress or to substance abuse or dependency. If the Manual is discontinued, we will use the replacement chosen by the APA, or by an organization which succeeds it.

As you can see, this definition is quite broad and could potentially encompass quite a few disabling conditions. Since the policy provision does not actually list out specific disorders, at best you would need to consult the APA manual, in addition to your disability policy, to find out what this provision actually means. And if your particular disorder does not fit neatly within the APA’s framework, you will likely have to go to court to determine whether your disorder falls within the policy’s definition of mental disorders and/or substance abuse disorders.

Also, because the definition is based upon the “most current edition” of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders published by the APA, the types of disorders covered by the limitation will change each time the APA publishes a new manual.

These are just a few of the reasons why disability claims involving mental disorders and substance abuse disorders can be particularly tricky. In the next post, we will look at an example of what a mental disorder/substance abuse disorder limitation provision looks like.

MetLife to Exit Individual Disability Insurance Market

MetLife, Inc. the fourth largest provider of long-term disability insurance by market share[1], is suspending sales of its individual disability insurance policies. In an internal memorandum to producers, MetLife Client Solutions Senior Vice President Kieran Mullins announced that the company would be suspending the individual disability insurance block of business effective September 1, 2016. In the memo, Mr. Mullins cites the goal of creating a new U.S. Retail organization for its insurance products and the “difficult, but strategic” decisions that led to the shutdown of their individual disability insurance product:

This was not an easy decision to make, given the growth and strength of our IDI business. However, we believe it is the best course of action for the immediate future. While there is tremendous opportunity in this market, the suspension provides us with the time and resources needed to properly separate the U.S. Retail business from MetLife. There is a significant amount of work to be done to retool existing systems – and implement new systems – that will ultimately provide the most value to our customers and sales partners in the years to come.

Insurance news websites are already speculating that the shutdown could put pressure on the remaining thirty-one companies selling individual disability insurance to raise premiums. Because MetLife controls such a substantial share of the individual disability insurance market, their departure effectively reduces the size of the pool in which the risk can be spread. Cyril Tuohy, writing for Insurancenewsnet.com, points to the move as an opportunity for the remaining companies in the market to innovate and attract the business MetLife will be leaving behind. The company’s departure will favor the insurers whose individual disability policies cater to physicians, dentists, and other high-income professionals, such as Guardian, Principal, The Standard, Ameritas and Northwestern Mutual.[2]

In an accompanying FAQ, MetLife assured producers that existing policies would not be affected by the change, and that they would continue to support policy increases by the terms of the Guaranteed Insurability Option, Automatic Increase Benefit, and Life Event riders. The memo also noted that MetLife would continue sales of its group, voluntary, and worksite disability products.

It is important to remember that even though MetLife must continue to service its existing policies, shutting down sales of new policies can still affect current policyholders. Absent the need to sell new policies, an insurer may have less incentive to provide customer service or avoid a complaint from the state insurance board. Additionally, once a block of business closes, the easiest way to maintain profitability of that product is through claims management. In real terms that is typically accomplished through claims denial and benefits termination. We discussed these very tactics in a 2012 blog post about Unum’s management of its closed block of individual disability insurance products.

If you have a MetLife individual disability insurance policy, pay close attention as the business focus shifts away from selling new policies and toward the management of existing policies. If you have a question or concern regarding your MetLife policy, contact our office.

[1]http://www.statista.com/statistics/216499/leading-long-term-disability-insurance-carriers-in-the-us/

[2]“Will MetLife’s Suspension Send DI Prices Soaring?” Cyril Tuohy, insurancenewsnet.com. http://insurancenewsnet.com/innarticle/agents-split-di-pricing-wake-metlife-suspension

Study Shows Increase in Long Term Disability Claim Denials

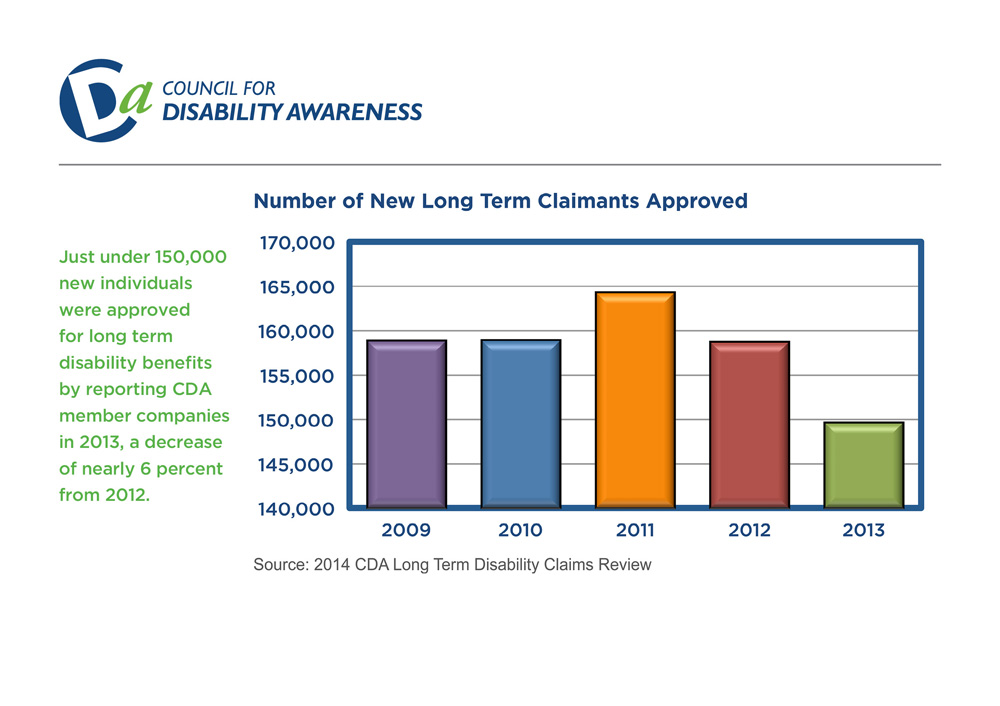

The most recent study conducted by the Council for Disability Awareness shows that long term disability claim approvals have declined in recent years:

In addition, 50% of the companies surveyed reported increased claim termination rates.

The companies surveyed included:

- Aetna

- AIG Benefit Solutions

- American Fidelity

- Ameritas

- Assurant Employee Benefits

- Disability RMS

- Guardian

- The Hartford

- Illinois Mutual

- Lincoln Financial Group

- MassMutual Financial Group

- MetLife

- Ohio National

- Principal Financial

- Prudential

- The Standard

- Sun Life Financial

- UnitedHealthcare

- Unum

References:

http://www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2014.asp

Long Term Disability by Gender, Age and Occupation

In previous posts, we have reviewed data collected by the Council for Disability Awareness related to long term disability claims.[1] In the next few posts, we are going to look at the most recent study conducted by the Council for Disability Awareness.

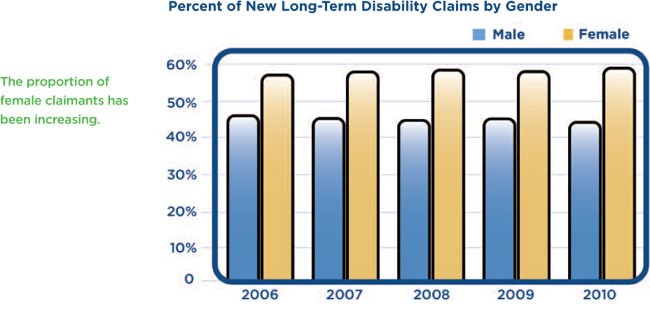

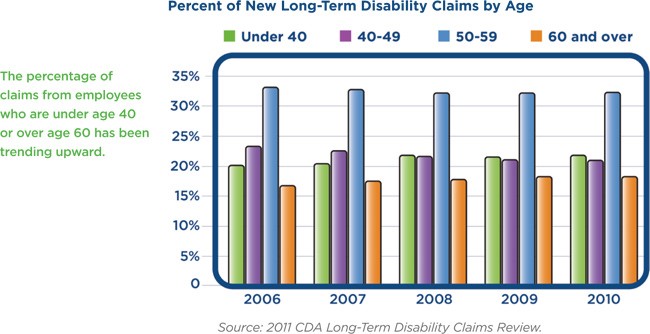

To begin, here are a few of the notable trends that the study revealed regarding the gender, age and occupation of long term disability claimants:

- The majority of long term disability claims are filed by women.

- The average age of long term disability claimants has increased in recent years, with the vast majority of claimants filing between the ages of 50 and 59.

- The number of in-force individual disability policies for business management and administration, physicians and dental professional occupation categories increased, while the number of in-force policies for sales and marketing professionals decreased.

References:

http://www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2014.asp

[1] The Council for Disability Awareness is “a nonprofit organization dedicated to educating the American public about the risk and consequences of experiencing an income-interrupting illness or injury.”

See http://www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2014.asp

Case Study: Interpreting Policy Language – Part 2

In Part 1 of this post, we started to look at the recent case Leonor v. Provident Life and Accident Company[1]. The key issue in this case was whether the disability policy language “the important duties” meant “all the important duties.” In Part 2 of this post, we will look at how the court addressed the parties’ arguments and see how the court ultimately resolved the dispute.

The Law

Under Michigan law, ambiguous words in a disability policy are construed in favor of the insured. A word or phrase is ambiguous if the word or phrase may “reasonably be understood in different ways.” Because of these rules, in order to win his case, the claimant, Leonor, did not have to come up with an interpretation that was superior to the interpretation offered by the disability insurer, Provident Life. Instead, Leonor merely had to establish that the policy language was ambiguous and then come up with a reasonable interpretation of the policy language that supported his disability claim for benefits.

The Analysis

The court began its analysis by recognizing that context is important when interpreting a contract. The court acknowledged that the definition of “residual disability” was obviously intended to be a less severe category of disability, and even acknowledged that the terms “total disability” and “residual disability” had to be mutually exclusive for the rest of the policy to make sense. Nonetheless, the court determined that the phrase “the important duties” was ambiguous.

By way of illustration, consider the following continuum, beginning with no limitations and ending at the inability to perform all of the important duties of an occupation.

|———————————–|———————————–|———————————–|

No Limitations Unable to Perform Unable to Perform Unable to Perform Some Duties Most Duties All Duties

Essentially, the court determined that the “residual disability” definition was broad enough to encompass individuals who could not perform “some” of the duties of their occupation, but was not broad enough to encompass individuals who could not perform “most” or “all” of the duties of their occupation. Thus, the policy language remained ambiguous because the “total disability” definition could still mean either the inability to perform “most” duties or the inability to perform “all” duties.

Next, the court determined that Leonor’s interpretation of the policy language was reasonable. The court explained that, under the rules of grammar, the definite plural does not necessarily apply to each thing in the group referred to. To support its position, the court noted that Provident Life’s own counsel argued at oral argument that its position was supported by “the rules of grammar” even though Provident Life’s counsel obviously did not mean to suggest that its position was supported by “all the rules of grammar.”

Finally, the court held that a claimant’s income is “far from dispositive” in disability cases. Specifically, the court determined that Leonor should not be penalized for earning more income after his injury than he did before the injury. The court noted that because investing in businesses is inherently risky, it was entirely appropriate for Leonor to insure himself against the loss of the guaranteed, steady income provided by the dental procedures.

The Decision

In the end, the court determined that Leonor was “totally disabled” under the policies because the phrase “the important duties” was ambiguous and Leonor had offered a reasonable application of the phrase that supported an award of benefits. The court ordered Provident Life to pay Leonor his benefits under the policy, plus 12% interest as a penalty for failing to pay the claim in a timely fashion.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates how the presence or absence of a single word in a policy can dramatically affect your ability to recover disability benefits. Even language that is not necessarily unfavorable, but merely ambiguous, can delay your recovery of benefits if you have to go to court to resolve a dispute with the insurer. For example, in the Leonor case, Leonor made his initial disability claim in July 2009, but the court did not conclusively establish he was entitled to disability benefits until June 2015—nearly six years later.

If possible, you should avoid ambiguous and unfavorable language when purchasing a policy. If you already have a disability policy, an experienced disability insurance attorney can review your policy and identify words or phrases that could impact your ability to recover disability benefits in a timely fashion.

[1] 790 F.3d 682 (6th Cir. 2015).

Case Study: Interpreting Policy Language – Part 1

Can the presence or absence of a single word in your disability policy determine whether you receive your disability benefits?

In the recent case Leonor v. Provident Life and Accident Company[1], the key issue was whether the policy language “the important duties” meant “all the important duties.” In Part 1 of this post, we will look at each party’s position in the case and examine why this policy language was so important. In Part 2 of this post, we will look at how the court addressed the parties’ arguments and see how the court ultimately resolved the dispute.

The Facts

In the Leonor case, the claimant, Leonor, was a dentist who could no longer perform dental procedures due to an injury and subsequent cervical spine surgery. Prior to the injury, Leonor spent approximately two-thirds of his time performing dental procedures, and spent the rest of his time managing his dental practice and other businesses he owned. After the injury, he no longer performed dental procedures; instead, he sought out other investment opportunities and devoted his time to managing his investments. Interestingly, Leonor’s income actually increased after he stopped performing dental procedures because his investments turned out to be very successful.

The Policy

Leonor’s disability policy provided for benefits if he became “totally disabled,” and defined “totally disabled” as follows:

“Total Disability” means that because of Injury or Sickness:

You are unable to perform the important duties of Your Occupation; and

You are under the regular and personal care of a physician.

Leonor’s policy also provided for benefits if he became “residually disabled,” and defined “residually disabled” as follows:

“Residual Disability,” prior to the Commencement Date, means that due to Injury or Sickness:

(1) You are unable to perform one or more of the important duties of Your Occupation; or

(2) You are unable to perform the important duties of Your Occupation for more than 80% of the time normally required to perform them; and

Your loss of Earning is equal to at least 20% of your prior earnings while You are engaged in Your Occupation or another occupation; and

You are under the regular and personal care of a Physician.

The Arguments

The insurer, Provident Life, argued that Leonor’s managerial duties were “important duties” of his occupation prior to his injury, and therefore Leonor was not “totally disabled” because he could still perform managerial duties in spite of his injury.

Leonor responded that the policy language only required him to be unable to perform “the important duties” of his occupation. He pointed out that Provident Life could have required him to be unable to perform “all the important duties” of his occupation. Since Provident Life did not include the word “all,” Leonor argued that it did not matter whether he could still perform managerial duties because he could no longer perform other “important duties” of his occupation—namely, performing dental procedures.

In response, Provident Life argued that, when read in context, “total disability” plainly meant the inability to perform “all the important duties” because the policy separately defined “residual disability” as being unable to perform “one or more of the important duties.” Thus, according to Provident Life there was already a category under the policy that covered individuals like Leonor who could not perform “some” of the important duties of their occupation. Provident Life also argued that Leonor should not receive total disability benefits because Leonor’s income after the injury was higher than it was prior to the injury.

Stay tuned for Part 2, to find out how the court addressed Principal Life’s arguments and resolved the dispute.

[1] 790 F.3d 682 (6th Cir. 2015).

Myelopathy: Part 2

In Part 1 of this post, we listed some of the symptoms and potential causes of myelopathy. In Part 2, we will discuss some of the methods used to treat myelopathy.

Methods of Treating Myelopathy

- Avoidance of activities that cause pain;

- Acupuncture;

- Using a brace to immobilize the neck;

- Physical therapy (primarily exercises to improve neck strength and flexibility);

- Various medication (including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), oral corticosteroids, muscle relaxants, anti-seizure medications, antidepressants, and prescription pain relievers);

- Epidural steroid injections (ESI);

- Narcotics, if pain is very severe;

- Surgical removal of bone spurs/herniated discs putting pressure on spinal cord;

- Surgical removal of portions of vertebrae in spine (to give the spinal cord more room); and

- Spinal fusion surgery.

Conclusion

Myelopathy can be severely debilitating, particularly for doctors and dentists. Obviously, any physician or dentist who is experiencing a loss of motor skills, numbness in hands and arms and/or high levels of chronic pain will not be able to effectively treat patients.

If you are experiencing any of these symptoms, you may want to ask your doctor to conduct tests to see if your spinal cord is being compressed. If you have myelopathy and the pain and numbness has progressed to the point where you can no longer treat patients effectively or safely, you should stop treating patients and consider filing a disability claim.

Myelopathy: Part 1

In previous posts, we have discussed a number of disabling conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, essential tremors, carpal tunnel syndrome, and fibromyalgia. In this post, we are going to talk about another serious condition that can severely limit a physician or dentist’s ability to practice—myelopathy. In Part 1, we will discuss some of the causes and symptoms of myelopathy. In Part 2, we will discuss some of the methods used to treat myelopathy.

What is Myelopathy?

Myelopathy is an overarching term used to describe any neurologic deficit caused by compression of the spinal cord.

The onset of myelopathy can be rapid or it can develop slowly over a period of months. In most cases, myelopathy is progressive; however, the timing and progression of symptoms varies significantly from person to person.

What Causes Myelopathy?

There are several potential causes of myelopathy, including:

- Bone fractures or dislocations due to trauma/injury;

- Inflammatory diseases/autoimmune disorders (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis);

- Structural abnormalities (e.g. bone spurs, disc bulges, herniated discs, thickened ligaments);

- Vascular problems;

- Tumors;

- Infections; and

- Degenerative changes due to aging.

Symptoms of Myelopathy

The symptoms of myelopathy will vary from case to case, because the nature and severity of the symptoms will depend on which level of the spine is being compressed—i.e. cervical (neck), thoracic (middle), or lumbar (lower)—and the extent of the compression.

Some of the symptoms of myelopathy include:

- Neck stiffness;

- Deep aching pain in one or both sides of neck, and possibly arms and shoulders;

- Grating or crackling sensation when moving neck;

- Stabbing pain in arm, elbow, wrist or arms;

- Dull ache/tingling/numbness/weakness in arms, hands, legs or feet;

- Position sense loss (i.e. the inability to know where your arms are without looking at them);

- Deterioration of fine motor skills (such as handwriting and the ability to button shirts);

- Lack of coordination, imbalance, heavy feeling in the legs, and difficulty walking;

- Clumsiness of hands and trouble grasping;

- Intermittent shooting pains in arms and legs (especially when bending head forward);

- Incontinence; and

- Paralysis (in extreme cases).

Case Study: Mental Health Disability Claims – Part 2

In Part 1 of this post, we started looking at a case involving a mental disability claim where the court reversed Unum’s claim denial under ERISA de novo review. In Part 2, we are going to look at how the same court determined the extent of claimant’s disability benefits.

Turning back to the Doe case we examined in Part 1, after the court reversed the denial, the parties could not agree on the amount of benefits the claimant was entitled to. In previous posts, we have discussed how many disability insurance policies have a mental health exclusion that limits recovery to a particular period—usually 2-3 years. Unfortunately for our claimant, he had such a provision in his disability policy, which provided that his “lifetime cumulative maximum benefit period for all disabilities due to mental illness” was “24 months.”[1]

Not surprisingly, Unum invoked this provision and asserted that it only had to pay benefits for a 24 month period. The court agreed, for several reasons:

- To begin, the policy defined “mental illness” as “a psychiatric or psychological condition classified in the [DSM], published by the American Psychiatric Association, most current at the start of disability.” All of claimant’s conditions (major depression, OCD, ADHD, OCPD, and Asperger’s) were classified in the DSM-IV.

- Claimant attempted to assert that his disability was not a “mental illness” because it was “biologically based.” Id. While this type of argument had been accepted by some other courts, the court in Doe determined that it was not convincing in this particular instance because the claimant’s policy expressly defined “mental illness” as a condition classified in the DSM-IV. The court also noted that DSM-IV itself notes that “there is much ‘physical’ in ‘mental’ disorders and much ‘mental’ in ‘physical’ disorders” Id.

- Accordingly, the court concluded that because the policy was “concerned only with whether a condition is classified in the DSM,” whether claimant’s conditions had “biological bases” was “immaterial.”

Thus, even though the Doe claimant was successful in obtaining a reversal of the claim denial, in the end, he only received 24 months of benefits due to the mental health exclusion.

If you are purchasing a new disability insurance policy, you will want to avoid such exclusions where possible. If you have a mental disability and are concerned about your chances of recovering benefits, an experienced disability insurance attorney can look over your policy and give you a sense of the likelihood that your disability claim will be approved, and the extent of the disability benefits you would be entitled to.

[1] See Doe v. Unum Life Ins. Co. of Am., No. 12 CIV. 9327 LAK, 2015 WL 5826696 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 5, 2015).

Case Study: Mental Health Disability Claims – Part 1

In a previous post, we have discussed how ERISA claims are different from other disability claims. We have also looked at an ERISA case involving “abuse of discretion” review. However, there is another type of review under ERISA—“de novo” review. Unlike abuse of discretion review, under de novo review, the court assesses the merits of the disability claim without affording any deference to the insurer’s decision. Whether your claim is governed by abuse of discretion review or de novo review will depend on the terms of your plan. An experienced disability attorney can look at your disability insurance policy and let you know which standard will apply.

In this post, we will be looking at two things. First, we will be looking at a case where the court reversed the denial of disability benefits under de novo review. Second, we will be looking at some of the issues that commonly arise in mental health disability claims. In Part 1, we will be looking at the initial determination made by the court regarding whether the claimant was entitled to disability benefits. In Part 2, we will be looking at how the court determined the amount of disability benefits the claimant was entitled to.

In Doe v. Unum Life Insurance Company of America[1], the claimant was a trial attorney with a specialty in bankruptcy law. After several stressful events, including his wife being diagnosed with cancer, claimant started experiencing debilitating psychological symptoms. The claimant was ultimately diagnosed with anxiety, major depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive personality disorder (OCPD), and Asperberger’s syndrome. He filed for long term disability benefits, but the insurer, Unum, denied his claim. The court reversed Unum’s claim denial under de novo review, for the following reasons:

- First, the court found the opinions and medical records of the claimant’s treatment providers to be “reliable and probative.” Id. More specifically, the court determined that claimant’s conditions fell within the expertise of the treating psychiatrist and that the psychiatrist’s conclusions were corroborated by neuropsychological testing.

- Second, the court determined that the opinions provided by Unum’s file reviewers were not credible or reliable. The court noted that while Unum’s in-house consultants claimed that the neuropsychological testing did not provide sufficient evidence of disability, the single outside independent reviewer hired by Unum concluded the opposite and determined that there was no evidence of malingering and that the tests were valid.

- Finally, the court rejected Unum’s argument that claimant’s psychiatrist should have provided more than a treatment summary. The court determined that this was “a problem of Unum’s own making,” because the evidence showed that Unum expressly stated in written correspondence that it was willing to accept a summary of care letter in lieu of the claimant’s original medical records.

Stay tuned for Part 2, where we will look at how much benefits the claimant actually ended up receiving.

[1] No. 12-CV-9327 LAK, 2015 WL 4139694, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. July 9, 2015).

Case Study: Abuse of Discretion Under ERISA

In previous posts, we have discussed how it is oftentimes harder to collect under ERISA policies. One of the primary reasons ERISA claims are more difficult is the fact that in most ERISA cases courts are required to defer to the insurer’s decision unless the insurer “abused its discretion.” Under the abuse of discretion standard, an insurer’s decision is only reversed if the claimant can demonstrate that the insurer’s actions were “arbitrary and capricious.” This is a high standard to meet.

While ERISA claims can be more difficult, particularly under the “abuse of discretion” standard, they are not impossible. Sometimes a court will determine that the insurer did, in fact, abuse its discretion. In this post, we will be looking at the recent court case Jalowiec v. Aetna Life Insurance Company[1] to illustrate some of the things that a court may find to be an abuse of discretion.

In Jalowiec, the claimant suffered from chronic migraine headaches, dizziness, nausea, vertigo, insomnia and fatigue after suffering a blow to the back of his head at a Tae Kwon Do event. After over a year of testing and treatment, the claimant was initially diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (“POTS”). Later on, claimant was diagnosed with an “unspecified disorder of autonomic nervous system.”

The insurer, Aetna, initially awarded the claimant short term disability benefits, but subsequently denied claimant’s claim for long term disability benefits. Ultimately, the court determined that Aetna’s denial of long term disability benefits was an abuse of discretion, for the following reasons:

- Aetna improperly classified claimant’s occupation as “sedentary,” which was not supported by substantial evidence.

- Aetna changed the classification of claimant’s occupation multiple times throughout the claims process, from “sedentary” at the short term disability phase, to “light’ at the initial stages of the long term disability claim, and then back to “sedentary” in order to deny the claim.

- Aetna relied on file reviews conducted by reviewers who were relying on incorrect and incomplete information about the claimant’s job classification (i.e. that the job was “sedentary,” not “light”).

- Aetna relied on file reviews conducted by reviewers who did not have the proper expertise to review claimant’s diagnosis of “unspecified disorder of autonomic nervous system.”

- Aetna relied on file reviews that were not based on informed consultation with the claimant’s treating physicians.

These are just a few examples of things that courts have found to be an “abuse of discretion” under ERISA. Remember, the law in each jurisdiction varies, so the courts in your state may not necessarily agree with the court in this case. An experienced disability insurance attorney should be able to give you a sense of whether a court would uphold or reverse your claim denial, under ERISA or otherwise.

[1] No. CV 14-4332 (DWF/LIB), 2015 WL 9294269, at *1 (D. Minn. Dec. 21, 2015).

Know Your Limits: How Issue and Participation Limits Affect Your Coverage

Recently, several disability insurers have decided to raise their Issue and Participation (I&P) limits. In this post we will discuss some of the potential ramifications of increased I&P limits.

What are Issue and Participation Limits?

The Issue Limit is the maximum amount of liability a single insurer will cover for a particular individual. The Participation Limit is the maximum amount of total coverage an insurer is willing to provide after factoring in the coverage that the individual is already receiving from other insurance companies. Usually your maximum monthly benefit is determined by your income, but some insurers allow professionals, such as physicians and dentists, to apply for default rates based on other factors such as occupation, years of experience, etc. Usually, an insurer’s I&P limits permit coverage in an amount that is approximately 40-65% of your actual monthly income.

Essentially, insurers use I&P limits to make it possible to collectively provide higher total benefits to high income earners, while at the same time ensuring that they are not over-insuring an individual.

What are the Ramifications of Higher Issue and Participation Limits?

In previous posts, we have talked about how in the 1980’s and early 1990’s, disability insurers aggressively marketed policies to doctors, dentists, and other high income earners. We’ve also discussed how, due to the emergence of managed care, doctors and dentists saw a significant decrease in income. The end result was that disabled doctors and dentists had policies that promised disability benefits that were equal to, or greater than, their modified salaries. When the insurance companies had to start paying the benefits they had promised, they lost hundreds of millions of dollars. This in turn led to insurance companies taking an aggressive stance toward claims involving high paying policies. Most disability insurers also stopped offering policies with high benefit limits.

Now, it appears that at least some insurance companies have come full circle and are once again marketing policies with high benefit limits. What does this mean? Now that insurers are beginning to raise I&P limits, it may be possible for you to obtain benefit amounts that are closer to your actual monthly income. Remember, as with any insurance, generally speaking, a higher benefit also means higher premiums. However, if you can afford it, it is usually better to have as much coverage as possible.

If insurers end up providing higher benefits again, it will be interesting to see if there is another corresponding spike in claim denials. If you do end up purchasing a high benefit policy, be sure to look it over carefully and make sure that there is not anything in it that would allow the insurance company to limit or deny your disability claim later on down the road. If you are unsure about whether you are being offered a good policy, an experienced disability insurance lawyer can review the disability policy and explain any complex provisions.

References:

http://www.virtual-strategy.com/2015/10/21/secura-consultants-highlights-new-benefit-levels-disability-insurance-coverage#axzz3ptYLroMT.

Build Your Own Insurance: What to Look for in a Policy

Recently, insurers have started to allow consumers to build and personalize their own disability insurance policies online. For instance, Guardian recently announced the launch of its online insurance quoting tool. According to Guardian, the tool “educates clients on the costs for various options based on age and occupation, demonstrates how adding or removing certain options affects pricing, and shows how to create the plan that best matches their individual needs.”[1]

If this “build your own insurance” concept catches on, consumers may have much more control over the terms of their policies than they have had in the past. Accordingly, in this post we are going to talk about things to look for in a policy, and some things to avoid in a disability insurance policy.

Things to Look for in a Policy

Generally speaking, here are a few things that you will want to look for when selecting a disability insurance policy:

- Make sure that the disability policy is a true “own occupation” policy.

- Make sure that the disability policy provides for lifetime benefits.

- If possible, add a specialty rider that clearly defines your own occupation as your specialty.

- Try and find a disability policy with a COLA (cost of living adjustment) provision. This provision will increase your potential disability benefits by adjusting for inflation as time passes.

- Make sure that you get the highest benefit amount you can afford. Remember, if you’re unable to practice, your monthly disability payments may be your only source of income.

Things to Avoid in a Policy

Generally speaking, here are a few things that you should avoid when selecting a disability insurance policy:

- “No Work” provisions that only provide disability benefits if you are unable to perform the material and substantial duties of your own occupation and you are not working in any other occupation.

- Substance abuse exclusions.

- Provisions requiring you to apply for Social Security benefits.

Remember, purchasing disability insurance is no different than any other significant purchase. Be sure to take your time and obtain quotes from multiple insurance companies before making a final decision.

For more information regarding what to look for in a policy, see this podcast interview where Ed Comitz discusses the importance of disability insurance with Dentaltown’s Howard Farran.

[1] See http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20151028005074/en/Guardian-Empowers-Consumers-Build-Disability-Insurance-Coverage.

Case Study: The Importance of Proper Documentation

In previous posts, we have discussed the importance of properly documenting your disability claim. From the moment you file your disability claim, most insurers begin collecting as much documentation as possible in the hopes that they can use the documentation to deny your initial claim, or terminate your disability benefits later on.

Oftentimes, disability benefits are terminated without warning. For example, an insurance company may conduct covert surveillance over an extended period of time, and then suddenly terminate your disability benefits once they feel that they have sufficient footage to assert that you are not disabled. If you are not consistently documenting the ongoing nature and extent of your disability, you may find yourself lacking sufficient evidence to contest a denial or termination of benefits.

For example, in the recent case Shaw v. Life Insurance Company of North America[1], the insurer refused to pay claimant her disability benefits. Although claimant saw multiple doctors and psychiatrists for PTSD and depression before filing her disability claim, the court ultimately found that the medical records she submitted were deficient, for several reasons.

First, even though claimant was asserting mental health claims, the claimant’s primary treatment provider was a family practice physician, not a psychologist or psychiatrist. Additionally, the court observed that the family practice physician’s records were “cursory, and contain[ed] minimal documentation of the frequency or intensity of [claimant’s] symptoms.” Id. To make matters worse, the claimant only saw the psychiatrists for a period of a few months, and the psychiatrists’ records showed that claimant had refused to follow the recommended treatment plan, which included both psychiatric medication and cognitive treatment.

The claimant attempted to supplement her medical records using a narrative letter she wrote describing her symptoms, along with several letters from family and friends. However, the court ultimately found the narratives unconvincing because there was a “significant potential for bias,” the severity levels described in the narratives conflicted with the psychiatrists reports, and claimant’s friends and family were not medical specialists or care providers and therefore could not diagnose claimant’s medical condition or assess claimant’s functional capacity. Id.

In the end, the court affirmed the denial of disability benefits, even under de novo review. Id.

What could the claimant have done better to avoid the denial? For one, she could have used a psychiatrist or psychologist as her primary treatment provider. She also could have followed the treatment plan recommended by her psychiatrists. Finally, she could have asked her physician to provide more thorough documentation.

Remember, courts will generally want to see medical records, not statements from friends and family. While such statements can be a useful way to provide background information, a court will want to see documentation of diagnosis and treatment by a health care provider. An experienced disability insurance attorney can help you review your medical records and determine if they are sufficient in comparison to the documentation that the insurance company will almost assuredly be collecting.

[1] No. CV1407955MMMFFMX, 2015 WL 6755187 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 4, 2015).

Exertion Levels: What They Are, and Why They Matter

The Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) contains definitions of various exertion levels that are used to place different jobs within categories based on the level of strength required to perform each job. You may have noticed these categories listed on claim forms, or referred to in functional capacity evaluation (FCE) reports or independent medical evaluations (IME) reports. In this post, we are going to look at what the various exertion levels are, and why they matter in the disability insurance context.

What Are the Exertion Levels?

The DOT lists five exertion levels—sedentary, light, medium, heavy, and very heavy. The DOT definitions for each exertion level are summarized below.

Sedentary Work (S)

Occasionally (i.e. up to 1/3 of the time) exerting up to 10 pounds of force and/or frequently (i.e. from 1/3 to 2/3 of the time) exerting a negligible amount of force to lift, carry, push, pull, or otherwise move objects, including the human body. Sedentary work involves sitting most of the time, but may involve occasional walking or standing for brief periods of time.

Light Work (L)

Occasionally exerting up to 20 pounds of force, and/or frequently exerting up to 10 pounds of force, and/or constantly (i.e. 2/3 or more of the time) exerting a negligible amount of force to move objects. Requires walking or standing to a significant degree, requires sitting most of the time but also involves pushing and/or pulling of arm or leg controls, and/or requires working at a production rate pace entailing the constant pushing and/or pulling of materials even though the weight of those materials is negligible.

Medium Work (M)

Occasionally exerting 20 to 50 pounds of force occasionally, and/or frequently exerting 10 to 25 pounds of force, and/or constantly exerting greater than negligible up to 10 pounds of force to move objects.

Heavy Work (H)

Occasionally exerting 50 to 100 pounds of force, and/or frequently exerting 25 to 50 pounds of force, and/or constantly exerting 10 to 20 pounds of force to move objects.

Very Heavy Work (V)

Occasionally exerting in excess of 100 pounds of force, and/or frequently exerting more than 50 pounds of force, and/or constantly exerting more than 20 pounds of force to move objects.

Why Do They Matter?

Insurers usually rely on the DOT exertion levels in ERISA claims or cases involving “any occupation” policies. First, the disability insurer will seek to establish that the claimant can work at the highest level of capacity possible. Then, the disability insurer will claim that the claimant can return to work performing any job within that category, and any lower categories.

Conversely, if the case involves an “own occupation” policy, the disability insurer will seek to establish that the claimant’s occupation required the lowest level of capacity. The disability insurer will then assert that the claimant’s disability is not severe enough to prevent the claimant from returning to his or her old job.

In either case, if the disability insurer feels that it can demonstrate that a claimant is capable of returning to work, it will likely deny the claim for disability benefits, or terminate existing disability benefits.

References:

http://www.occupationalinfo.org/appendxc_1.html

Case Study: Can You Sue Your Insurer For Emotional Distress?

At least one court thinks so. In Daie v. The Reed Grp., Ltd.[1], the claimant was denied long term disability benefits under an ERISA plan. Instead of merely asking the court to reverse the denial of disability benefits (a result that can be difficult to achieve under ERISA), claimant filed a complaint in state court alleging intentional infliction of emotional distress.

The claimant asserted that the insurer “repeatedly engaged in extreme and outrageous conduct with the aim of forcing plaintiff to drop his claim and return to work.” Id. More specifically, the claimant alleged that the insurer had falsely claimed the claimant was “lying” about his disability and “exaggerating” his symptoms. Id. According to the claimant, the insurer had also urged claimant to take “experimental medications,” induced claimant to “increase his medications,” forced claimant “to undergo a litany of rigorous medical examinations without considering their results,” and pressured claimant “to engage in further medical testing that it knew would cause . . . pain, emotional distress and anxiety.” Id.

The insurer filed a motion to dismiss, arguing that ERISA preempted claimant from bringing the state law claim. The court denied the motion to dismiss for two reasons. First, the court determined that the claim was based on “harassing and oppressive conduct independent of the duties of administering an ERISA plan.” Id. Second, the court determined the insurer had a “duty not to engage in the alleged tortious conduct” that existed “independent of defendants’ duties under the ERISA plan.” Id.

The federal court then sent the case back to state court, where, as of the date of this post, the state court has not yet determined whether claimant should be awarded damages for emotional distress.

At this point, this ruling has only been adopted by the District Court, and not the Court of Appeals, so it is not binding upon other courts. However, it could potentially persuade other courts to recognize similar claims. It will be interesting to see how many other courts follow suit, and whether this ruling will ultimately be adopted by courts at the appellate level.

[1] No. C 15-03813 WHA, 2015 WL 6954915, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 10, 2015).

The Reality of Addiction: Physicians Are Susceptible Too

We’ve discussed the prevalence of depression and stress in physicians, but what about addiction? While physicians are just as likely as the general public to become dependent upon alcohol and illegal drugs, they are more likely to abuse prescription drugs. A survey of 55 physicians that were being monitored by their state physician health programs for problems relating to drug and alcohol abuse showed that 38 (69%) abused prescription drugs. While certainly concerning, this is not necessarily surprising, as physicians have far greater access to prescription drugs than the average person.

Compounding this issue is the stigma associated with substance abuse. Oftentimes, those who do not suffer from substance addiction believe that drugs and alcohol are something that people can quit easily, and that substance abuse can be solved by a quick trip to a rehab facility. But in many cases, substance abuse is more than mere recreational use of medications. In some cases, those who abuse prescription drugs may be trying to relieve stress or self-medicate chronic physical and/or emotional pain. In other cases, substance abuse may be a result of the phenomenon called “presenteeism”—doctors may be taking the medication simply because they believe it is the only way to continue working in spite of an illness, impairment, or disability.

How can medical professionals with substance addiction get help? One way is to seek confidential treatment to avoid the scrutiny of a medical board or coworkers. Confidential programs can be both outpatient and inpatient, with inpatient programs usually lasting around one to three months. After treatment, patients are able to continue recovering by completing 12–step programs, like Alcoholics Anonymous. However, this treatment option has similar relapse rates to the general public: nearly half of patients relapse in the first year.

A second road to recovery is physician health programs. These programs actively monitor patients after treatment for a period of five years by conducting drug testing, surveillance and behavioral assessments. This path may be difficult for physicians to come to term with after keeping their addiction hidden. However, going through the physician health programs boasts a much higher success rate of 78% (only 22% tested positive during the 5-year monitoring period), and roughly 70% of medical professionals who pursue this method of treatment are still working and retain their licenses.

If you, or a physician you know, struggles with substance dependency, we encourage you to seek out appropriate help. If you are a physician with a painful disability, you should not put your patients at risk by attempting to work through the pain or by seeking to dull the pain with self-medication. If you have disability insurance, you should contact an experienced disability insurance attorney. He or she will be able to guide you through the claims process and help you secure the benefits that you need without putting yourself or your patients at risk.

REFERENCES:

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/819223_3.

DOL Proposes Changes to ERISA

In prior posts, we have noted that employer-sponsored disability plans are generally governed by ERISA. We have also discussed some of the challenges claimants may face when filing a disability claim under ERISA.

Recently, the Department of Labor (DOL) proposed some new regulations that could make filing a disability claim under ERISA more claimant-friendly. If finalized, the regulations will change several aspects of the claims process under ERISA. Some of the most notable changes are as follows:

- Insurers will have to hire medical experts based solely upon professional qualifications (as opposed to hiring an expert because the expert is known for supporting disability denials of benefits).

- At both the initial claim stage and the appeal stage, insurers will have to provide a detailed explanation for their denial, including their bases for disagreeing with the claimant’s treating physician, the Social Security Administration, and/or other insurers who are paying benefits under other policies the claimant may have.

- Insurers will have to include the internal rules/guidelines/protocols/standards used to deny the disability claim, or expressly state that such criteria do not exist.

- Insurers will have to notify claimants at the initial claim phase that the claimant is entitled to receive and review a copy of their claim file (right now, insurers only have to do this at the appeal stage).

- During the appeal stage, insurers must automatically provide claimants with any new information that was not considered at the initial claim stage so that the claimants can review and respond to the new information.

- If an insurer violates the new rules (and it is not a minor violation) claimants can file suit immediately and the court must review the dispute de novo (i.e. without giving special deference to the insurer’s claim decision).

Some of these rules have already been established by case law, but as of right now, they are not uniformly applied across the country. If the DOL moves forward and finalizes the regulations, disability insurers and plan administrators will have to uniformly comply with these new rules when administrating ERISA claims.