Thinking About A Policy Buyout?

How Lump Sum Settlements Work: Part 1

Lump sum buyouts are a frequent source of questions from our clients and potential clients. With that in mind, the next few posts will address different aspects of the buyout process.

Buyouts typically occur in one of two situations: 1) after you’ve been on claim for several years, or 2) after a lawsuit has been filed. This blog post will focus on the first scenario.

Lump sum buyouts that occur outside of litigation normally won’t occur unless and until the insurance company decides that you are totally and permanently disabled under the policy definition. Typically, the disability insurer won’t consider whether this is the case until you’ve been on claim for at least two years. If the insurer determines that you’re totally and permanently disabled, it will then determine whether it makes sense financially for the company to offer you a percentage of your total future benefits rather than keep paying your monthly benefits for the entire duration of your claim.

To understand how the insurance company calculates whether a buyout is in its financial interest, you should understand how insurance company reserves work. The purpose of reserves is to ensure that the insurance company has the resources to fulfill its obligations to policyholders even if the company has financial difficulties. Thus, disability insurers are required by state regulators to keep a certain amount of money set aside, or “reserved,” to pay future claims. Any money required to be kept in a reserve is money that the insurer can’t spend on other things or pay out in dividends. The amounts required to be kept in the reserve are determined by the state, depending on factors like how much the monthly benefit is and how long the claim is expected to last.

For a disability insurance claim, a graph of the required reserve amount over time looks like a Bell curve: low at the beginning, highest in the middle, and low again towards the end of the benefit period. The ideal time for a settlement, from an insurance company’s perspective, is at or just before the high middle point–typically about five to seven years into the claim, depending on the claimant’s age and the duration of the benefit period. At this point, the company is having to set aside the highest amount of money in the reserve.

If the insurance company can pay you a percentage of your total future benefits, it can not only save money in the long run, but it can release the money in the reserve. The disability insurer can then use those funds for other purposes, including providing dividends for its investors. In addition, the insurance company will save all of the administrative expenses it was putting towards monitoring your disability claim.

In the next post, we’ll address how and why buyouts occur after a lawsuit has been filed.

Should Women Pay More for Disability Insurance? Part 2

In a previous post, we discussed how a woman with the same age, job and health history as a man can end up paying an average of 25% (and in some cases, 60%) more for the same level of disability insurance protection. We also discussed how some insurance companies raise premiums based on conditions unique to one’s sex, such as pregnancy.

When we first addressed this issue, the Massachusetts legislature was considering a bill that prohibited insurers from charging higher rates to women than to men. At the time, Massachusetts law prohibited insurance companies from using race and religion as rating factors when determining the cost of insurance, but there was no law against using gender as a rating factor.

Recently, the Massachusetts Senate voted to approve a budget amendment adding gender to other rating factors that insurance companies are not allowed to consider when determining the cost of premiums. The bill passed by a wide margin: 32 senators in favor of the amendment, and only 6 senators voting against the amendment.

It will be interesting to see if, in the future, other states follow suit and start to pass laws requiring insurance companies to give men and women the same premium rates for the same level of disability coverage.

References:

http://www.masslive.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/05/senate_votes_to_exclude_gender.html

Long Term Disability by Diagnosis

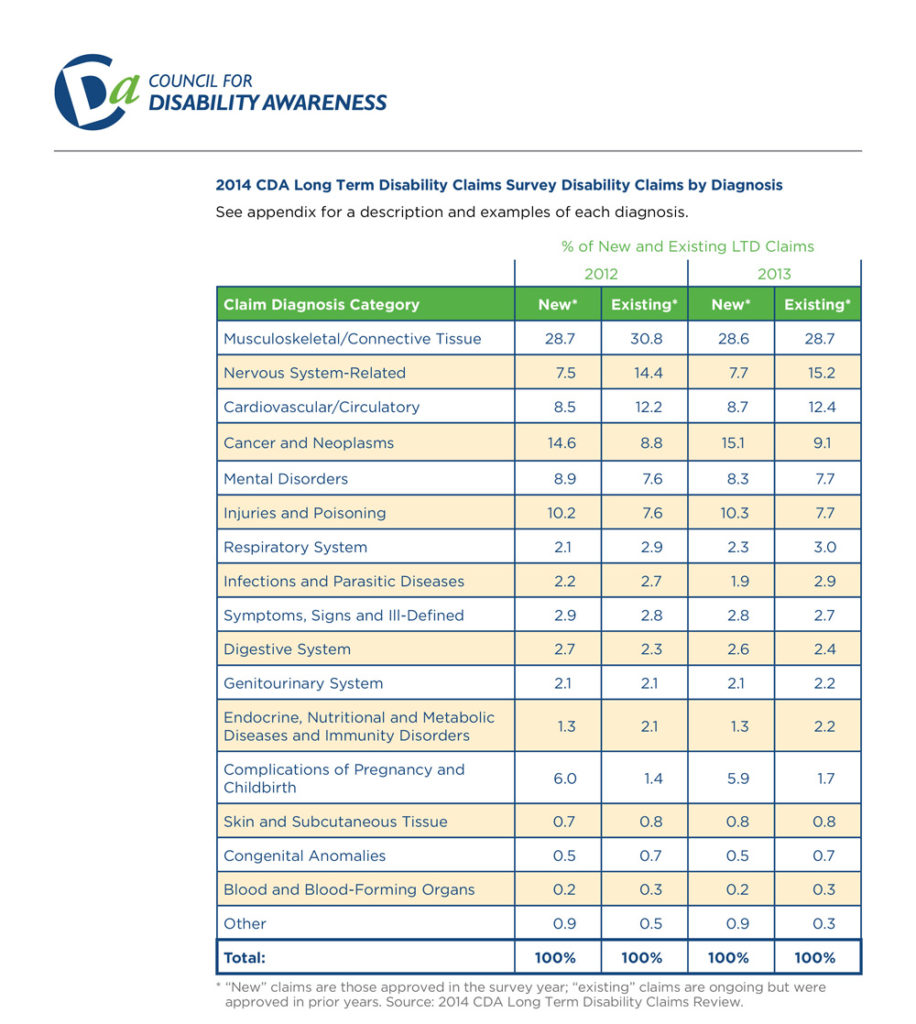

In previous posts, we have been looking at the findings from the most recent study on long term disability claims conducted by the Council for Disability Awareness. In this post we will be looking at the types of diagnoses associated with long term disability claims, and which types of claims are most common.

As you can see from the chart above, the most common type of both new and existing long term disability is musculoskeletal disorders—a category which includes neck and back pain caused by degenerative disc disease and similar spine and joint disorders.

This is particularly noteworthy because physicians and dentists, who often have to maintain uncomfortable static postures for several hours each day, are very susceptible to musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, claims involving musculoskeletal disorders can be challenging, because oftentimes there is little objective evidence to verify the pain. If you suffer from degenerative disc disease or a similar disorder, an experienced disability insurance attorney can explain how to properly document your disability claim to the insurance company.

References:

http://www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2014.asp

Case Study: Factual Disability v. Legal Disability – Part 3

In the last post, we discussed the facts of the court case Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company v. Jefferson[1]. In that case, the court was asked to determine whether a clinical psychologist whose license had been suspended was entitled to disability benefits. In this post, we will discuss how the court ultimately ruled, and go over some takeaways from this case.

The Court’s Ruling

As explained in the last post, the key question was whether Dr. Jefferson’s legal disability (i.e. the suspension of his license to practice psychology) happened before the onset of Dr. Jefferson’s factual disability (i.e. his depression). In the end, the court determined that Dr. Jefferson was not entitled to disability benefits for the following reasons:

- Dr. Jefferson’s claim form stated that he was not disabled until April 29, 1990, which was two days after the licensing board revoked his license.

- Although Dr. Jefferson later claimed that his depression went as far back as May 1989, the court determined that such claims were inconsistent with:

-

- Jefferson’s representations to the licensing board that he was a “highly qualified and competent psychologist”;

-

- The fact that Dr. Jefferson had been consistently seeing patients up until the day his license was revoked; and

-

- The fact that Dr. Jefferson had scheduled patients during the month following the licensing board’s hearing.

Thus, under the circumstances, the evidence showed that Dr. Jefferson’s was not entitled to benefits because his legal disability preceded his factual disability.

Takeaways

Dr. Jefferson’s case provides a good example of the challenges that can arise in a disability claim if the claimant has lost his or her license. Here are some of the major takeaways from this case:

Be Precise When Filling Out Claim Forms. The date you list as the starting date of your disability can be very significant. Take your time when filling out claim forms, and make sure that the date you provide is accurate and consistent with the other information you are submitting with your claim forms. It is always a good idea to double check everything on the form at least once after you have completed it, to make sure that you did not make a mistake.

Recognize that Your Claim Will Not Be Evaluated in a Vacuum. Other proceedings—such as board hearings—can directly impact your disability claim. You should always assume that anything you say in such a proceeding will at some point end up in front of the insurance company. This is particularly problematic when, as in Dr. Jefferson’s case, the goals of the other proceeding are inconstant with the goals of the disability claim. In such a situation, you may have to decide which goal is more important to you. An experienced disability insurance attorney can help you assess the strengths and weaknesses of each available option so that you can make an informed decision.

Do NOT Engage in Activities that Place Your License in Jeopardy. Losing a license that you worked hard for several years to obtain is not only emotionally devastating, it can severely limit your options going forward. Even if you have a disability policy, it is very difficult to successfully collect on a disability claim if your license has been revoked or suspended. Once again, if you find yourself in Dr. Jefferson’s position, you should talk with an experienced attorney who can help you determine what your available options are, if any.

[1] 104 S.W.3d 13, 18 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2002).

Case Study: Factual Disability v. Legal Disability – Part 2

In the last post, we discussed the distinction between “factual” and “legal” disability and why that distinction matters. In this post, we will begin looking at a court case involving “factual” and “legal” disability. Specifically, in this post we will begin looking at the facts of the case and the test that the court applied. In Part 3, we will see how the court ultimately ruled.

The Facts

In the case of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company v. Jefferson[1], the court assessed whether Dr. Jefferson—a clinical psychologist—was entitled to disability benefits. Here are the key facts of the case:

- From October 1987 to February 1989, Dr. Jefferson had an affair with a former patient.

- When Dr. Jefferson’s wife found out about the affair, she filed a complaint with Dr. Jefferson’s licensing board.

- During the hearings in front of the licensing board, Dr. Jefferson argued that he was a competent psychologist, and that he should be permitted to continue to see patients.

- On April 27, 1990, the licensing board permanently revoked Dr. Jefferson’s license to practice psychology, effective as of May 15, 1990. On appeal, a chancery court reduced the permanent revocation to an eight year suspension ending on May 15, 1998.

- Up until the day his license was revoked, Dr. Jefferson continued to see patients and schedule future patients.

- On October 1, 1990, Dr. Jefferson filed a claim under his disability policy, claiming that he was disabled due to “major depression.”

- On his claim form, Dr. Jefferson listed the beginning date of his disability as April 29, 1990. Later on, Dr. Jefferson attempted to submit evidence that he had been depressed as early as May 1989.

The Court’s Test

As a threshold matter, the Court determined that the suspension of Dr. Jefferson’s license was a “legal disability” and assumed for the sake of argument that Dr. Jefferson’s “major depression” was a “factual disability.” As explained in Part 1 of this post, courts generally hold that disability policies only cover factual disabilities, not legal disabilities. However, the court’s decision becomes more difficult when a claimant like Dr. Jefferson has both a legal disability and a factual disability.

Although different courts approach this situation in different ways, here is the test that the court came up with in Dr. Jefferson’s case:

- Step 1: Determine which disability occurred first.

- Step 2: Apply the following rules:

-

- Rule # 1: If the legal disability occurred first, the claimant is not entitled to benefits.

-

- Rule # 2: If the factual disability occurred first, the claimant is entitled to benefits, if the claimant can prove the following three things:

-

-

- The factual disability has medical support.

- The onset of the factual disability occurred before the legal disability.

- The factual disability actually prevented or hindered the claimant from engaging in his or her profession or occupation.

-

In the next post, we will discuss how the court decided this case. In the meantime, now that you have the key facts and the court’s test, see if you can guess how the court ultimately ruled.

[1] 104 S.W.3d 13, 18 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2002).

Case Study: Factual Disability v. Legal Disability – Part 1

In the next few posts we will be looking at the distinction between “factual” and “legal” disability. In Part 1, we will discuss the difference between a factual and a legal disability, and why that distinction matters. In Parts 2 and 3, we will look at an actual court case involving “factual” and “legal” disability.

What is “Factual Disability”?

Factual disability refers to incapacity caused by illness or injury that prevents a person from being physically or mentally able to engage in his or her occupation. This is the type of disability that most people think of in connection with a disability claim.

What is “Legal Disability”?

Legal disability is a broad term used to encompass all circumstances in which the law does not permit a person to engage in his or her profession, even though he or she may be physically and mentally able to do so. Here are some examples:

- Incarceration;

- Revocation or suspension of a professional license;

- Surrendering a professional license as part of a plea agreement or to avoid disciplinary action; and

- Practice restrictions imposed by a licensing board.

Why the Distinction Matters

In sum, someone with a “factual disability” is mentally or physically unable to engage in their profession. In contrast, someone with a “legal disability” is not allowed to engage in their profession. Courts have repeatedly held that disability insurance policies provide coverage for factual disabilities, but not for legal disabilities.

If a claimant has both a factual and legal disability, things become more complicated. In the next few posts, we will look at an example of how one court determined whether someone with both a factual and legal disability was entitled to benefits.

Online Underwriting – Tips to Avoid Potential Pitfalls

Recently, several disability insurers have started to introduce new online applications in an effort to make purchasing disability insurance more convenient. Some of them even offer automated underwriting and instant approval of your application. In connection with the online applications, insurers are also providing more flexible options regarding benefit amounts and benefit periods.

While online applications will likely make purchasing disability insurance more convenient, here are some tips to keep in mind and some pitfalls to avoid.

- Don’t neglect to shop around. While it will certainly take less time to just apply to the first website you come across, you should always look at what multiple companies are offering before you apply for disability benefits. While it may not seem like it at the time, the decision to purchase disability insurance may be one of the most important decisions in your life if you end up becoming disabled. So make sure to take the time to research what your options are, so that you can be sure to get the best disability insurance policy you are able to.

- Do the research. If you are merely interacting with a computer screen, you will not be able to ask questions about particular policy provisions. Consequently, you should take the time to do outside research so that you know exactly what to look for and what to avoid in a disability insurance policy.

- Don’t sacrifice important provisions for convenience or affordability. There are certain provisions that every doctor and dentist should have in their policy, such as an own occupation provision. If the online policy does not offer the provisions you need, don’t settle for the sake of convenience or affordability. Remember, if you end up becoming disabled, you will not just want any disability policy—you will want the best disability policy.

- Take your time when you are filling out your application. Most disability insurance policies contain language that allows the insurer to void the policy if you make material misstatements in your application. Many people tend to rush through online applications, particularly if their priority is convenience. Make sure that you double check your answers before you submit the application, to ensure that everything you are submitting is accurate.

- Periodically reevaluate your coverage. If your initial goal is affordability, make sure that you periodically reevaluate your coverage to ensure that it is still sufficient for your needs. Many people initially apply for low benefit policies and neglect to increase their benefits amounts later on when they can afford to pay higher premiums. Consequently, if they become disabled, their benefit amount ends up covering only a small fraction of their prior income.

These tips are particularly important for physicians and dentists to remember when applying for disability insurance, because insurance companies are particularly aggressive towards disability claims filed by doctors and dentists. Additionally, many doctors and dentists are accustomed to a high level of income. Physicians and dentists who do not purchase enough disability coverage and later become disabled can find themselves unable to meet their obligations and care for their family, even if their disability claim is approved. Additionally, as we have discussed in previous posts, in some cases, a single word in a disability insurance policy can determine whether you receive benefits.

So remember, purchasing disability insurance is not something that should be taken lightly. Take your time, and get the best policy you can.

What is a Pain Journal and Why Are They Important?

In previous posts, we have discussed the importance of properly documenting your disability. In this post we are going to discuss one way you can document your disability—pain journals.

A pain journal is exactly what is sounds like—a journal in which you document your pain levels and symptoms each day. Creating this sort of record will not only provide you with documentation when filing your disability claim, but will also allow you to effectively communicate with your treatment providers regarding your symptoms, so that they can provide you with appropriate care. Oftentimes, depending on your disability, you will go several days or weeks without speaking to your treatment providers. A pain journal can help you easily recall and communicate to your treatment provider everything that has happened since you last met with them.

Tips for Creating a Pain Journal

When creating a pain journal, you want to be as specific as possible so that your record is complete. You also want to make sure that you describe your plain clearly, so that you will be able to understand what you meant when you refer back to your journal.

Here are a few things you might consider documenting in your journal:

- The location of the pain.

- The level of the pain (if you use a numeric scale, be sure to also describe the scale).

- The duration of the pain.

- Any triggers to the pain.

- Any medications you are taking.

- Whether the medications you are taking are effective or have any adverse side effects.

- Any other symptoms in addition to the pain.

When filling out your pain journal, you may have a hard time coming up with a description that fits the type of pain you are experiencing, since all pain is not the same. However, you should avoid the temptation to document your pain in a generic way. The type of pain you are experiencing is just as important as your pain levels, and it is something that your disability insurer will likely ask you to describe.

To that end, here is a list of adjectives that are commonly used to describe pain:

Cutting; Burning; Cramps; Knots; Deep; Pulsing; Sharp; Shooting; Tender; Tight; Surface; Throbbing; Acute; Agonizing; Chronic; Dull; Gnawing; Inflamed; Raw; Severe; Stabbing; Stiff; Stinging

Sample Pain Journals:

American Pain Foundation Form:

American Cancer Society Form:

Peace Health Medical Group Form:

The Four Functions of Insurance

In this post, we are going to discuss the four functions of an insurance company.

Introduction – The Promise

Insurance is not like any other business. Rather than selling a tangible product that you receive immediately upon paying for it, insurance companies are selling an important promise—a promise of protection, security and peace of mind if something goes wrong.

When you buy a car, you give someone money and you take a car home. When you buy groceries, you pay money and get your groceries. Insurance is different. With insurance, you give them money and trust, and hope and pray that you never have to collect.

The Four Functions of Insurance

The activities of an insurance company can be divided into four major functions:

1. Actuarial

The actuarial department is concerned with what kind of promise the company is going to sell and how much the promise should cost. Essentially, the actuaries’ role is to analyze the financial consequences of risk and price the company’s product in a way that will allow the company to make a profit. For example, an actuary working for a car insurance company might calculate the risk that potential customers will be in a car accident, and then adjust premium amounts to account for that risk so that the insurer can pay accident claims and still make money.

2. Marketing

The marketing department is concerned with how to get people to buy the promise being sold. They design ads and employ sales people. Basically, this department’s goal is to get people interested in buying the promise.

3. Underwriting

The underwriting department determines who the company should sell the promise to. Underwriters review applications and assess whether the company should allow applicants to purchase the promise. For example, the underwriting department of a life insurance company might review health questionnaires submitted by applicants to assess whether the level of risk is low enough to provide life insurance to the applicant.

4. Claims

The claims department’s role is to process and pay legitimate claims. While the first three departments are very much concerned about profitability, the claims department is not supposed to consider company profitability when adjusting a claim. If the actuaries made a mistake and sold a product that is costing the company too much money, the product was not marketed correctly, or if underwriting was too lax, the company is supposed to pay legitimate claims and bear the loss.

Conclusion

As we have discussed in previous posts, an insurance company has a legal obligation to treat its customers fairly and deal with its customers in good faith. Ideally, the disability insurance claim process should be simple. You should inform the company that you meet the standards of the contract, provide certification from a doctor of that fact, and collect your disability benefits. It is not supposed to be an adversarial process.

Unfortunately, in instances where one or all of the first three departments mess up, some insurance companies improperly shift the burden of making a profit onto the claims department. This, in turn, transforms the claims process into an adversarial process.

If you have an experienced disability attorney involved from the outset of your disability claim, your attorney can monitor the insurance company to make sure that they are complying with their legal obligations. If you have already filed a disability claim, but believe that your insurer is not properly processing your claim, an experienced attorney can review the insurer’s conduct and determine whether the disability insurer is acting in bad faith.

New Methods of Surveillance: Part 2 – Drones

In Part 1 of this post, we discussed “stingrays”—a relatively new technology that is becoming more and more common. In Part 2, we will be discussing another new technology that is becoming increasingly prevalent as a surveillance tool—drones.

What is a “Drone”?

The term “drone” is a broad term that refers to aircrafts that are not manned by a human pilot. Some drones are controlled by an operator on the ground using remote control. Other drones are controlled by on-board computers and do not require a human operator. Drones were initially developed primarily for military use. Recently, drones have also been utilized for a wide range of non-military uses, such as aerial surveying, filmmaking, law enforcement, search and rescue, commercial surveillance, scientific research, surveying, disaster relief, archaeology, and hobby and recreational use.

How Does Drone Surveillance Work?

Typically, drones are connected to some type of control system using a data link and a wireless connection. Drones can be outfitted with a wide variety of surveillance tools, including live video, infrared, and heat-sensing cameras. Drones can also contain Wi-Fi sensors or cell tower simulators (aka “stingrays”) that can be used to track locations of cell phones. Drones can even contain wireless devices capable of delivering spyware to a phone or computers.

Conclusion

Over the past few years, several new methods of surveillance have been developed. These new technologies create a high risk of abuse by disability insurance companies, and as they become more and more commonplace and affordable, that risk will only increase. Unfortunately, in the area of surveillance, the law has not always been able to keep up with the pace of technology. In many respects, the rules regarding the use of new surveillance technologies remain unclear. Consequently, the most effective way to guard against intrusions of privacy is to be aware of the expanding abilities of existing technology, because you never know when someone could be conducting surveillance.

References:

ACLU Website: https://theyarewatching.org/technology/drones.

New Methods of Surveillance: Part 1 – “Stingrays”

In previous posts, we have discussed how insurance companies will hire private investigators to conduct surveillance on disability claimants. In the next two posts, we will be discussing some modern surveillance technologies that most people are not very familiar with – “stingrays” and drones.

What is a “Stingray”?

A “stingray” is a cell site simulator that can be used to track the location of wireless phones, tablets, and computers—basically anything that uses a cell phone network.

How Does Stingray Surveillance Work?

A “stingray” imitates cell towers and picks up on unique signals sent out by individuals attempting to use the cell phone network. The unique signal sent out is sometimes referred to as an International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) and it consists of a 12 to 15 digit number.

Once the “stingray” connects to a device’s signal, it can collect information stored on the device. Usually the information collected is locational data, which is then used to track the movement of individual carrying the device.

Additionally, some “stingray” devices can intercept and extract usage information, such as call records, text messages, and Internet search history, from devices it connects to. Some “stingrays” are even able to intercept phone call conversations and deliver malicious software to personal devices.

Stay tuned for Part 2, where we will discuss drone surveillance.

References:

ACLU Website: https://theyarewatching.org/technology/stingray.

Deciphering Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Policy Exclusions – Part 2

In Part 1, we looked at how disability insurance companies broadly define mental disorders and substance abuse. In this post, we will be looking at a sample mental disorder and substance abuse limitation provision.

What Does a Mental Disorder and Substance Abuse Limitation Look Like?

Here is a sample limitation provision from an actual disability policy (this provision is taken from the same policy containing the definition of “mental disorders and/or substance abuse disorders” discussed in Part 1):

maximum indemnity period means the maximum length of time for which benefits are to be paid during any period of total disability (see the Policy Schedule on Page 1). Benefits will not be paid beyond the policy anniversary that falls on or most nearly after your sixty-seventh birthday, or for 24 months, if longer, except as provided by this policy. In addition to any limitations described above, the maximum indemnity period for a disability due to a mental disorder and/or substance abuse disorder is also subject to the following limitations: (a) The lifetime maximum indemnity period is 24 months; (b) the 24-month limitation also applies to all supplementary benefits payable by virtue of your disability due to a mental disorder and/or substance abuse disorder; (c) any month in which benefits are paid for a mental disorder and/or substance abuse disorder (regardless of whether paid under the base policy any supplementary benefits or both) shall count toward the 24-month limitation; (d) this limitation applies to this policy and all supplementary benefits under this policy.

Note that this provision is not entitled “mental disorder limitation” or “substance abuse limitation.” Instead, it is entitled “maximum indemnity period.” In fact, this provision is actually part of the policy’s definition section, and not the main part of the policy—highlighting the importance of carefully reviewing the definitions in your disability insurance policy.

Note also that this particular provision provides that any month in which disability benefits are paid counts against the 24 month limit. So, for example, if you received disability benefits for a period of 12 months in connection with a substance abuse related disability, and subsequently returned to work, the next time you needed to file a claim related to a mental disorder or substance abuse, you could only receive a maximum of 12 months of disability benefits.

Conclusion

When purchasing a disability policy, watch out for mental disorder and substance abuse exclusions and limitations. Always be sure to ready your policy carefully so that you understand the scope of the protection you are purchasing. If you already have a disability policy, an experienced disability insurance attorney can review your policy and determine whether it contains any mental disorder or substance abuse limitations that might limit your ability to collect disability benefits under your policy.

Deciphering Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Exclusions – Part 1

In previous posts, we have discussed how many disability policies contain mental disorder and/or substance abuse exclusions that either prevent claimants from collecting disability benefits under their policies, or severely limit claimants’ right to collect—usually to 24 months or less.

Sometimes, it can be hard to tell if your disability insurance policy contains such an exclusion. Policy language can be difficult to decipher, and it becomes even more difficult in cases where the terms of the exclusion are contained within multiple provisions of the disability policy.

In the next few posts, we are going to discuss mental disorder and substance abuse exclusions. In Part 1, we will look at an example of how insurance companies define mental disorders and substance abuse. In Part 2, we will look at an example of a mental disorder and substance abuse limitation provision.

How Do Insurance Company’s Define Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse?

Each policy’s definition varies, depending on the insurance company. Here is a sample definition taken from an actual insurance policy:

mental disorders and/or substance abuse disorders mean any of the disorders classified in the most current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Such disorders include, but are not limited to, psychotic, emotional, or behavioral disorders, or disorders relatable to stress or to substance abuse or dependency. If the Manual is discontinued, we will use the replacement chosen by the APA, or by an organization which succeeds it.

As you can see, this definition is quite broad and could potentially encompass quite a few disabling conditions. Since the policy provision does not actually list out specific disorders, at best you would need to consult the APA manual, in addition to your disability policy, to find out what this provision actually means. And if your particular disorder does not fit neatly within the APA’s framework, you will likely have to go to court to determine whether your disorder falls within the policy’s definition of mental disorders and/or substance abuse disorders.

Also, because the definition is based upon the “most current edition” of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders published by the APA, the types of disorders covered by the limitation will change each time the APA publishes a new manual.

These are just a few of the reasons why disability claims involving mental disorders and substance abuse disorders can be particularly tricky. In the next post, we will look at an example of what a mental disorder/substance abuse disorder limitation provision looks like.

MetLife to Exit Individual Disability Insurance Market

MetLife, Inc. the fourth largest provider of long-term disability insurance by market share[1], is suspending sales of its individual disability insurance policies. In an internal memorandum to producers, MetLife Client Solutions Senior Vice President Kieran Mullins announced that the company would be suspending the individual disability insurance block of business effective September 1, 2016. In the memo, Mr. Mullins cites the goal of creating a new U.S. Retail organization for its insurance products and the “difficult, but strategic” decisions that led to the shutdown of their individual disability insurance product:

This was not an easy decision to make, given the growth and strength of our IDI business. However, we believe it is the best course of action for the immediate future. While there is tremendous opportunity in this market, the suspension provides us with the time and resources needed to properly separate the U.S. Retail business from MetLife. There is a significant amount of work to be done to retool existing systems – and implement new systems – that will ultimately provide the most value to our customers and sales partners in the years to come.

Insurance news websites are already speculating that the shutdown could put pressure on the remaining thirty-one companies selling individual disability insurance to raise premiums. Because MetLife controls such a substantial share of the individual disability insurance market, their departure effectively reduces the size of the pool in which the risk can be spread. Cyril Tuohy, writing for Insurancenewsnet.com, points to the move as an opportunity for the remaining companies in the market to innovate and attract the business MetLife will be leaving behind. The company’s departure will favor the insurers whose individual disability policies cater to physicians, dentists, and other high-income professionals, such as Guardian, Principal, The Standard, Ameritas and Northwestern Mutual.[2]

In an accompanying FAQ, MetLife assured producers that existing policies would not be affected by the change, and that they would continue to support policy increases by the terms of the Guaranteed Insurability Option, Automatic Increase Benefit, and Life Event riders. The memo also noted that MetLife would continue sales of its group, voluntary, and worksite disability products.

It is important to remember that even though MetLife must continue to service its existing policies, shutting down sales of new policies can still affect current policyholders. Absent the need to sell new policies, an insurer may have less incentive to provide customer service or avoid a complaint from the state insurance board. Additionally, once a block of business closes, the easiest way to maintain profitability of that product is through claims management. In real terms that is typically accomplished through claims denial and benefits termination. We discussed these very tactics in a 2012 blog post about Unum’s management of its closed block of individual disability insurance products.

If you have a MetLife individual disability insurance policy, pay close attention as the business focus shifts away from selling new policies and toward the management of existing policies. If you have a question or concern regarding your MetLife policy, contact our office.

[1]http://www.statista.com/statistics/216499/leading-long-term-disability-insurance-carriers-in-the-us/

[2]“Will MetLife’s Suspension Send DI Prices Soaring?” Cyril Tuohy, insurancenewsnet.com. http://insurancenewsnet.com/innarticle/agents-split-di-pricing-wake-metlife-suspension

Study Shows Increase in Long Term Disability Claim Denials

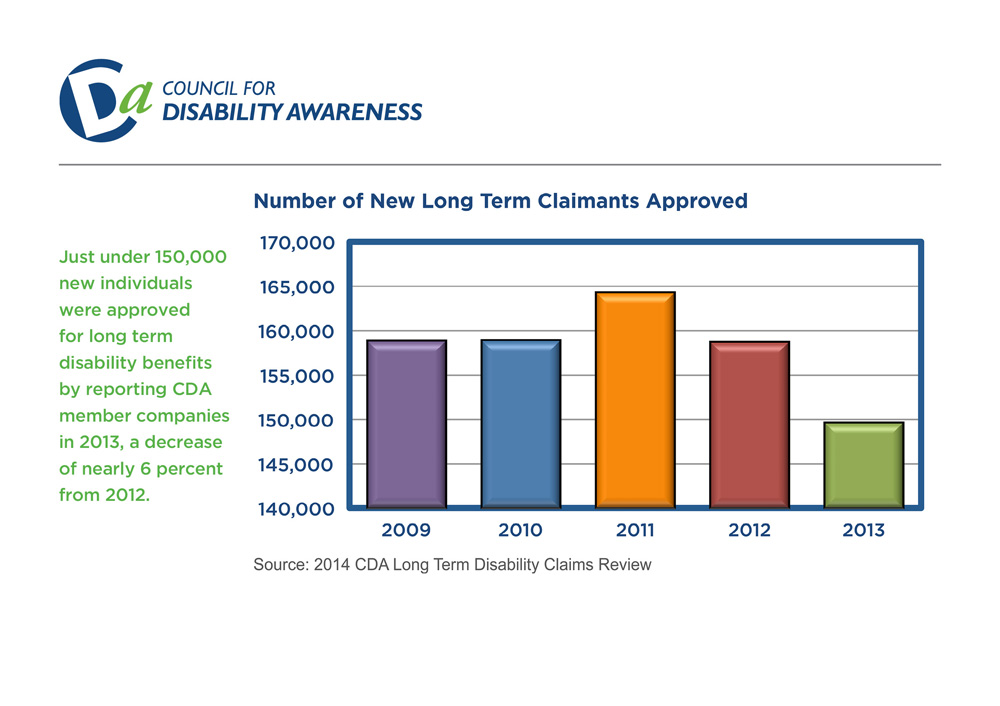

The most recent study conducted by the Council for Disability Awareness shows that long term disability claim approvals have declined in recent years:

In addition, 50% of the companies surveyed reported increased claim termination rates.

The companies surveyed included:

- Aetna

- AIG Benefit Solutions

- American Fidelity

- Ameritas

- Assurant Employee Benefits

- Disability RMS

- Guardian

- The Hartford

- Illinois Mutual

- Lincoln Financial Group

- MassMutual Financial Group

- MetLife

- Ohio National

- Principal Financial

- Prudential

- The Standard

- Sun Life Financial

- UnitedHealthcare

- Unum

References:

http://www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2014.asp

Long Term Disability by Gender, Age and Occupation

In previous posts, we have reviewed data collected by the Council for Disability Awareness related to long term disability claims.[1] In the next few posts, we are going to look at the most recent study conducted by the Council for Disability Awareness.

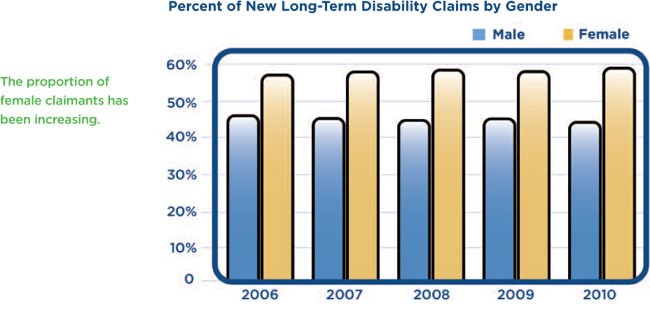

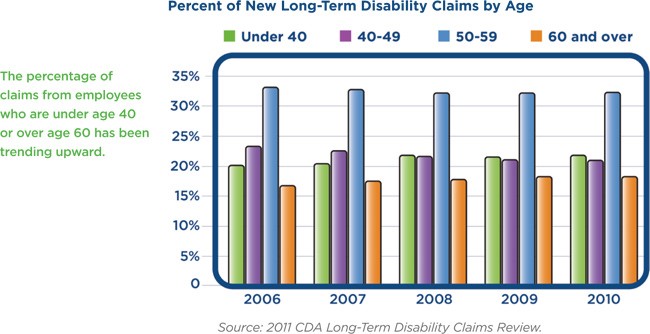

To begin, here are a few of the notable trends that the study revealed regarding the gender, age and occupation of long term disability claimants:

- The majority of long term disability claims are filed by women.

- The average age of long term disability claimants has increased in recent years, with the vast majority of claimants filing between the ages of 50 and 59.

- The number of in-force individual disability policies for business management and administration, physicians and dental professional occupation categories increased, while the number of in-force policies for sales and marketing professionals decreased.

References:

http://www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2014.asp

[1] The Council for Disability Awareness is “a nonprofit organization dedicated to educating the American public about the risk and consequences of experiencing an income-interrupting illness or injury.”

See http://www.disabilitycanhappen.org/research/CDA_LTD_Claims_Survey_2014.asp

Case Study: Interpreting Policy Language – Part 2

In Part 1 of this post, we started to look at the recent case Leonor v. Provident Life and Accident Company[1]. The key issue in this case was whether the disability policy language “the important duties” meant “all the important duties.” In Part 2 of this post, we will look at how the court addressed the parties’ arguments and see how the court ultimately resolved the dispute.

The Law

Under Michigan law, ambiguous words in a disability policy are construed in favor of the insured. A word or phrase is ambiguous if the word or phrase may “reasonably be understood in different ways.” Because of these rules, in order to win his case, the claimant, Leonor, did not have to come up with an interpretation that was superior to the interpretation offered by the disability insurer, Provident Life. Instead, Leonor merely had to establish that the policy language was ambiguous and then come up with a reasonable interpretation of the policy language that supported his disability claim for benefits.

The Analysis

The court began its analysis by recognizing that context is important when interpreting a contract. The court acknowledged that the definition of “residual disability” was obviously intended to be a less severe category of disability, and even acknowledged that the terms “total disability” and “residual disability” had to be mutually exclusive for the rest of the policy to make sense. Nonetheless, the court determined that the phrase “the important duties” was ambiguous.

By way of illustration, consider the following continuum, beginning with no limitations and ending at the inability to perform all of the important duties of an occupation.

|———————————–|———————————–|———————————–|

No Limitations Unable to Perform Unable to Perform Unable to Perform Some Duties Most Duties All Duties

Essentially, the court determined that the “residual disability” definition was broad enough to encompass individuals who could not perform “some” of the duties of their occupation, but was not broad enough to encompass individuals who could not perform “most” or “all” of the duties of their occupation. Thus, the policy language remained ambiguous because the “total disability” definition could still mean either the inability to perform “most” duties or the inability to perform “all” duties.

Next, the court determined that Leonor’s interpretation of the policy language was reasonable. The court explained that, under the rules of grammar, the definite plural does not necessarily apply to each thing in the group referred to. To support its position, the court noted that Provident Life’s own counsel argued at oral argument that its position was supported by “the rules of grammar” even though Provident Life’s counsel obviously did not mean to suggest that its position was supported by “all the rules of grammar.”

Finally, the court held that a claimant’s income is “far from dispositive” in disability cases. Specifically, the court determined that Leonor should not be penalized for earning more income after his injury than he did before the injury. The court noted that because investing in businesses is inherently risky, it was entirely appropriate for Leonor to insure himself against the loss of the guaranteed, steady income provided by the dental procedures.

The Decision

In the end, the court determined that Leonor was “totally disabled” under the policies because the phrase “the important duties” was ambiguous and Leonor had offered a reasonable application of the phrase that supported an award of benefits. The court ordered Provident Life to pay Leonor his benefits under the policy, plus 12% interest as a penalty for failing to pay the claim in a timely fashion.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates how the presence or absence of a single word in a policy can dramatically affect your ability to recover disability benefits. Even language that is not necessarily unfavorable, but merely ambiguous, can delay your recovery of benefits if you have to go to court to resolve a dispute with the insurer. For example, in the Leonor case, Leonor made his initial disability claim in July 2009, but the court did not conclusively establish he was entitled to disability benefits until June 2015—nearly six years later.

If possible, you should avoid ambiguous and unfavorable language when purchasing a policy. If you already have a disability policy, an experienced disability insurance attorney can review your policy and identify words or phrases that could impact your ability to recover disability benefits in a timely fashion.

[1] 790 F.3d 682 (6th Cir. 2015).

Case Study: Interpreting Policy Language – Part 1

Can the presence or absence of a single word in your disability policy determine whether you receive your disability benefits?

In the recent case Leonor v. Provident Life and Accident Company[1], the key issue was whether the policy language “the important duties” meant “all the important duties.” In Part 1 of this post, we will look at each party’s position in the case and examine why this policy language was so important. In Part 2 of this post, we will look at how the court addressed the parties’ arguments and see how the court ultimately resolved the dispute.

The Facts

In the Leonor case, the claimant, Leonor, was a dentist who could no longer perform dental procedures due to an injury and subsequent cervical spine surgery. Prior to the injury, Leonor spent approximately two-thirds of his time performing dental procedures, and spent the rest of his time managing his dental practice and other businesses he owned. After the injury, he no longer performed dental procedures; instead, he sought out other investment opportunities and devoted his time to managing his investments. Interestingly, Leonor’s income actually increased after he stopped performing dental procedures because his investments turned out to be very successful.

The Policy

Leonor’s disability policy provided for benefits if he became “totally disabled,” and defined “totally disabled” as follows:

“Total Disability” means that because of Injury or Sickness:

You are unable to perform the important duties of Your Occupation; and

You are under the regular and personal care of a physician.

Leonor’s policy also provided for benefits if he became “residually disabled,” and defined “residually disabled” as follows:

“Residual Disability,” prior to the Commencement Date, means that due to Injury or Sickness:

(1) You are unable to perform one or more of the important duties of Your Occupation; or

(2) You are unable to perform the important duties of Your Occupation for more than 80% of the time normally required to perform them; and

Your loss of Earning is equal to at least 20% of your prior earnings while You are engaged in Your Occupation or another occupation; and

You are under the regular and personal care of a Physician.

The Arguments

The insurer, Provident Life, argued that Leonor’s managerial duties were “important duties” of his occupation prior to his injury, and therefore Leonor was not “totally disabled” because he could still perform managerial duties in spite of his injury.

Leonor responded that the policy language only required him to be unable to perform “the important duties” of his occupation. He pointed out that Provident Life could have required him to be unable to perform “all the important duties” of his occupation. Since Provident Life did not include the word “all,” Leonor argued that it did not matter whether he could still perform managerial duties because he could no longer perform other “important duties” of his occupation—namely, performing dental procedures.

In response, Provident Life argued that, when read in context, “total disability” plainly meant the inability to perform “all the important duties” because the policy separately defined “residual disability” as being unable to perform “one or more of the important duties.” Thus, according to Provident Life there was already a category under the policy that covered individuals like Leonor who could not perform “some” of the important duties of their occupation. Provident Life also argued that Leonor should not receive total disability benefits because Leonor’s income after the injury was higher than it was prior to the injury.

Stay tuned for Part 2, to find out how the court addressed Principal Life’s arguments and resolved the dispute.

[1] 790 F.3d 682 (6th Cir. 2015).

Myelopathy: Part 2

In Part 1 of this post, we listed some of the symptoms and potential causes of myelopathy. In Part 2, we will discuss some of the methods used to treat myelopathy.

Methods of Treating Myelopathy

- Avoidance of activities that cause pain;

- Acupuncture;

- Using a brace to immobilize the neck;

- Physical therapy (primarily exercises to improve neck strength and flexibility);

- Various medication (including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), oral corticosteroids, muscle relaxants, anti-seizure medications, antidepressants, and prescription pain relievers);

- Epidural steroid injections (ESI);

- Narcotics, if pain is very severe;

- Surgical removal of bone spurs/herniated discs putting pressure on spinal cord;

- Surgical removal of portions of vertebrae in spine (to give the spinal cord more room); and

- Spinal fusion surgery.

Conclusion

Myelopathy can be severely debilitating, particularly for doctors and dentists. Obviously, any physician or dentist who is experiencing a loss of motor skills, numbness in hands and arms and/or high levels of chronic pain will not be able to effectively treat patients.

If you are experiencing any of these symptoms, you may want to ask your doctor to conduct tests to see if your spinal cord is being compressed. If you have myelopathy and the pain and numbness has progressed to the point where you can no longer treat patients effectively or safely, you should stop treating patients and consider filing a disability claim.

Myelopathy: Part 1

In previous posts, we have discussed a number of disabling conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, essential tremors, carpal tunnel syndrome, and fibromyalgia. In this post, we are going to talk about another serious condition that can severely limit a physician or dentist’s ability to practice—myelopathy. In Part 1, we will discuss some of the causes and symptoms of myelopathy. In Part 2, we will discuss some of the methods used to treat myelopathy.

What is Myelopathy?

Myelopathy is an overarching term used to describe any neurologic deficit caused by compression of the spinal cord.

The onset of myelopathy can be rapid or it can develop slowly over a period of months. In most cases, myelopathy is progressive; however, the timing and progression of symptoms varies significantly from person to person.

What Causes Myelopathy?

There are several potential causes of myelopathy, including:

- Bone fractures or dislocations due to trauma/injury;

- Inflammatory diseases/autoimmune disorders (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis);

- Structural abnormalities (e.g. bone spurs, disc bulges, herniated discs, thickened ligaments);

- Vascular problems;

- Tumors;

- Infections; and

- Degenerative changes due to aging.

Symptoms of Myelopathy

The symptoms of myelopathy will vary from case to case, because the nature and severity of the symptoms will depend on which level of the spine is being compressed—i.e. cervical (neck), thoracic (middle), or lumbar (lower)—and the extent of the compression.

Some of the symptoms of myelopathy include:

- Neck stiffness;

- Deep aching pain in one or both sides of neck, and possibly arms and shoulders;

- Grating or crackling sensation when moving neck;

- Stabbing pain in arm, elbow, wrist or arms;

- Dull ache/tingling/numbness/weakness in arms, hands, legs or feet;

- Position sense loss (i.e. the inability to know where your arms are without looking at them);

- Deterioration of fine motor skills (such as handwriting and the ability to button shirts);

- Lack of coordination, imbalance, heavy feeling in the legs, and difficulty walking;

- Clumsiness of hands and trouble grasping;

- Intermittent shooting pains in arms and legs (especially when bending head forward);

- Incontinence; and

- Paralysis (in extreme cases).